By Richard Edwards

Robin Smith was back at the home of Hampshire cricket last week – a county that still views him as one of their favourite adopted sons.

Smith, alongside the likes of Shane Warne, Mark Nicholas and Nick Pocock, attended a former captains’ dinner on Tuesday night as part of a series of celebrations in the run-up to the return of Test cricket to the South Coast for the first time since 2014.

As England struggle to find answers to the collapses that have blighted their cricket in recent years, there would have been plenty of supporters filing into the Ageas Bowl wishing that Smith was still in his pomp.

As it is, the now 53-year-old will have to make do with a seat in the stands.

Between 1988 and 1992, Smith was routinely all that stood between England and another batting capitulation.

With his swirling arms, blinking eyes and high octane squats, even Smith’s warm-up bristled with intent. His Test average of 43.67 is an indication of his enduring excellence at a time when the lifespan of most England batsmen was measured in single figure Test appearances.

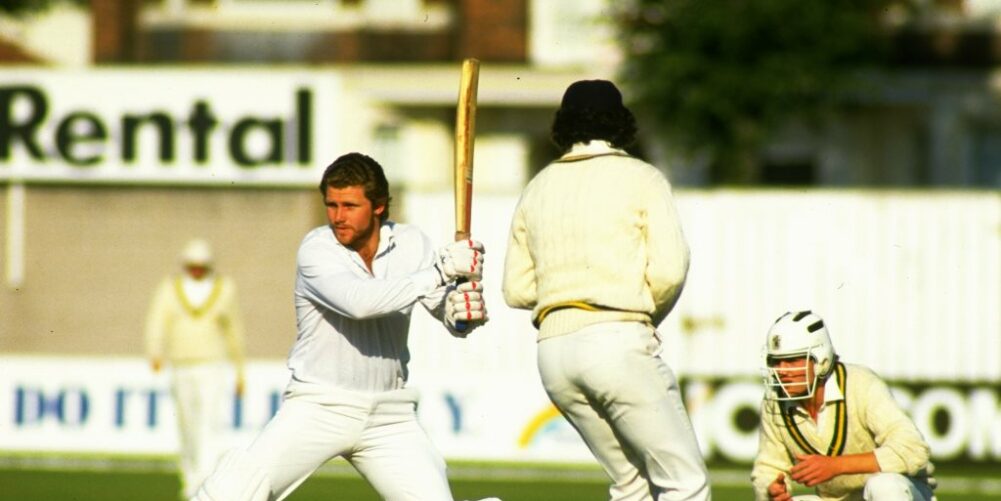

It was the Benson and Hedges Cup Final in the summer of 1988 when Smith gave the England selectors a forceful nudge. His 38 against Derbyshire was a thrilling exhibition of strokeplay against a bowling attack consisting of Devon Malcolm, Ole Mortensen and Michael Holding.

Smith’s trademark square cuts took the breath away as Hampshire walloped Kim Barnett et al in Hampshire’s first ever Lord’s final.

Just weeks later he found himself facing the West Indies pace quartet in a Headingley Test that would be Chris Cowdrey’s first and last as England captain. Smith scored 38 and put on 103 with Allan Lamb – the first of countless memorable partnerships between the naturalised South Africans – and generally demonstrated the kind of fight and attacking flair that England had sorely lacked for so long.

He scored his first Test half century in the following match at the Oval, almost single-handedly defying a West Indies attack of Malcolm Marshall, Curtly Ambrose, Courtney Walsh and Winston Benjamin.

If that series gave notice of his ability, the 1989 Ashes announced his arrival as one of the world’s leading top order batsmen. As England wickets tumbled, Smith stood tall among the rubble, not just defying the likes of Terry Alderman, Geoff Lawson and Merv Hughes, but putting them on his favourite place – the back foot.

His crowning glory came in the fourth Test at Old Trafford, as Alan Lee described in The Times:

“Out of the ugly wreckage of another high-speed batting collapse emerged a survivor to console this stricken England team. Robin Smith scored his first century of a Test career which is starting to flourish just as those of many around him are withering.”

It was as accurate a summation of a situation as you’re likely to find – just ask Tim Curtis and Tim Robinson, who proceeded Smith’s increasingly confident stride to the wicket.

Unlike his team-mates at the top of the order, the Australian attack had no answer to his belligerent square cuts and over-my-dead-body defence.

In short, this Durban-born star was heaven sent at a time when England’s failings with the bat were being exposed time and again, not just by Australia but by most other teams.

Now, 30 years after his debut, Smith’s eventual average would be viewed as eminently respectable. Back then, it was little short of remarkable. And the thing that made him stand out was the fact that he did it when it mattered most – not just when England were up against it but also against the very best.

Smith averaged 61 in that Ashes series. England’s next highest for play-ers who played more than one Test was Jack Russell’s 39. It was an extraordinary exhibition of one man’s will and one he repeated time and again.

Against the West Indies in 1991, he averaged 83 as England drew the series 2-2. Without Smith, quite simply, that would never have happened.

Against all the odds, Smith was now widely viewed as one of the world’s finest batsmen.

That he never played beyond the 1995/96 tour of South Africa is an indication of England’s muddled thinking. He never saw eye to eye with Ray Illingworth, an England coach who once reduced him to tears, but the nagging feeling remains Smith still had plenty to offer as he moved into his mid-30s.

That he didn’t is England’s loss, as is the fact that he has been largely lost to the sport in this country. He would have hoped to witness a battling display in his own mould on home turf yesterday.