Derek Pringle looks at the effects Packer, Stamford and Modi have had on the way our sport is played and broadcast

There can be a thin line between visionary and villain, especially in such an emotive field as sport. Sometimes the monikers are interchangeable depending on one’s perspective, a flip-flop the following trio have all experienced in their bid to change cricket and its status quo.

Kerry Packer, Allen Stanford and Lalit Modi have all brought big ideas to cricket though ones with a bittersweet legacy depending on your palate.

Packer, the son of Frank Packer who founded a publishing empire in Sydney, Australia, was a man used to getting what he wanted. Indeed, it was his rebuffed attempt to win the TV rights to Australian cricket for his newly-minted Channel Nine station which caused him to set up his own cricket circus in direct opposition to official cricket.

With characteristic chutzpah, he lured the world’s best players with promises of increased rewards.

It was a ruthless move that left countries like England, Australia and the West Indies not only shorn of their captains – Tony Greig, Greg Chappell and Clive Lloyd all signed up – but their leading players.

The best cricketers of Pakistan and South African were also signed up.

After winning a seven-week court case against the cricket establishment in late 1977, Packer’s World Series Cricket played its first SuperTest between Australia and the Rest of the World. Floodlit cricket, day-night matches, coloured clothing, white balls and black sightscreens arrived in season two, innovations that, along with drop-in pitches, remain in place today.

Big crowds flocked to watch, especially the day-night cricket, though by 1980 it was over. Packer had secured the TV rights to Australian cricket for three years and a marketing deal for ten. Although no lover of cricket (Packer preferred polo and gambling), and therefore no philanthropist to the game, his transformation of a cricket system trapped in aspic has benefitted professional cricketers and revolutionised both the way the game is played and covered on TV.

As Richie Benaud said when Packer died in 2005: “It’s because of what happened then, cricket is so strong now.”

But while that is undeniably true it has also created a landscape where the international game is at the mercy of TV money, and we have all seen, with the recent carve-up of ICC’s broadcasting rights by the Big Three, how that can distort even the best intentions.

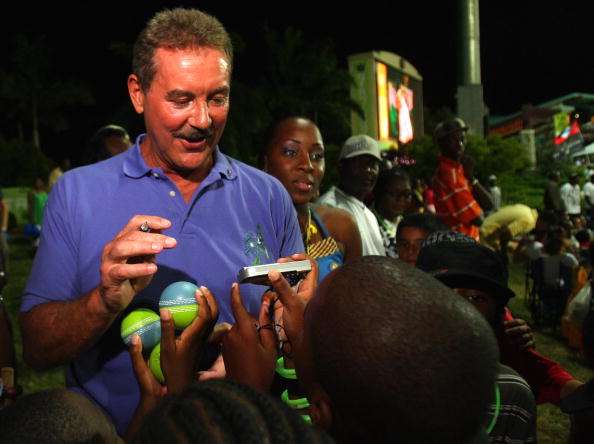

Allen Stanford was an American financier who knew nothing of cricket until he set up a bank in the West Indies, initially on Montserrat (where he was eventually told to take a hike) and then on Antigua. Indeed, his influence on that island became so great it is said he employed one in three of the workforce causing it be known as Stanfordland.

Noting how cricket was woven into the social fabric of the English-speaking Caribbean, Stanford set up a T20 competition in his name.

Its popularity reinvigorated cricket in the region, emboldening Stanford to spread his influence within the game.

It was from this desire coupled with that of an England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) trying to prevent their leading players being lured away by the new Indian Premier League (IPL), which led to the Stanford Challenge between West Indies and England for a winner-takes-all pot worth U$20 million. While Packer’s methods were brusque and direct, Stanford’s were crass and vulgar. Landing a helicopter on the Nursery at Lord’s and then unveiling a perspex box full of dollar notes (most were fake like the man himself) were so tacky the ECB have still not lived them down.

The challenge went ahead with Stanford photographed bouncing Matt Prior’s wife on his knee, but England lost.

The joy of the winning West Indies team, playing as the Stanford Allstars, was not universal, especially for those players who re-invested their winnings with him.

Within a year it was revealed that Stanford had expedited the biggest fraud in American history by running a billion dollar Ponzi scheme, a crime for which he was sentenced to 110 years in jail.

What boggles the mind is that the ECB or anyone else involved with Stanford did not sniff the warning signs or, if they did, why they turned a blind eye.

When he first began to woo the ECB, I asked a banker friend of mine, who had worked in Texas, to email his contacts there and ask them what they made of Stanford.

To a man they flagged up warnings, with several suspecting Ponzi schemes albeit without strong evidence. If the ECB did undertake due diligence with Stanford, it must have been done with ear muffs and a blindfold.

Stanford’s legacy should not really be countenanced though there are still those in the Caribbean reluctant to condemn him out of hand.

After all, during those few years when his T20 competition strutted its stuff, West Indies’ cricket really began to dance again.

Like Packer and Stanford, Lalit Modi hails from a wealthy background. Also like them, he possessed no great interest in cricket. But he does have a flair for business and a drive for bold schemes, two factors crucial in setting up the IPL, which he did at the behest of the Board of Cricket Control for India (BCCI) in 2007.

According to James Astill in his fine book the The Great Tamasha, about the rise of cricket in modern India, Modi personally secured most of the franchise holders for IPL, after studying how American sports made money, and hired the International Management Group to run it. He also brokered the U$1billion TV deal, and delivered the main sponsors.

Although not the first T20 competition in India (the Indian Cricket League predated it), IPL did have the major advantage of BCCI’s backing.

A brash upturn in the Indian economy also helped its establishment as did India’s timely victory in the 2007 World T20 trophy where they beat arch rivals Pakistan in the final, but it remains a staggering achievement nonetheless.

As IPL’s chairman and commissioner, Modi ran the most exciting and popular cricket brand the world has seen since the Ashes and the 50-over World Cup.

Cricket as soap opera may sound hackneyed but Modi’s model has since been copied around the world many times.

England may have been the true originators of T20 but you would not know it, such has been the incredible heat, noise and money coming from IPL.

Accusations of alleged financial irregularity saw Modi ousted from his role in 2010, claims he says are trumped up.

The fight to clear his name, from exile in London, remains ongoing. What is not really up for argument is that he changed cricket’s commercial landscape forever.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, Friday April 15 2016