The year is 2058 – the 50th anniversary of DRS in Test cricket – and the tannoy crackles into life at Lord’s. “Ladies and gentleman, just to remind you that during today’s tea interval Hawkeye will be outside the MCC Shop signing copies of his autobiography: Machines Are Only Human After All (Duckworth & Lewis, £19.19).”

Whether or not robots eventually rise up and take over the world (Hotspot for Prime Minister, perhaps, and Snicko president of the ICC) one day in the future – just as there are no more survivors of soldiers who fought in the trenches during World War I – there won’t be a cricket spectator in the land who was born before the Decision Review System.

If Dickie Bird has made a will leaving any of his bits to medical science, what could be more appropriate than his right index finger being pickled in a jar, and placed on display behind glass in the Lord’s Museum. A relic – alongside a pair of those rubber spiked batting gloves and a curved bat – of cricket’s dim and distant past.

On the assumption that DRS is here to stay (and with an England v Pakistan cricket series upon us it is probably compulsory if the two countries are to avoid closing embassies and recalling diplomats) it is interesting to look back at its unsophisticated beginnings, which in England came with the first television line decision back in 1993.

It was during a Benson & HedgesCup match between Surrey and Lancashire at the Oval, and so keen were the umpires to give the new experiment an airing, that when Wasim Akram was run out by what the officials admitted later was at least a yard, they referred it upstairs anyway just to get it up and running.

However, when the third umpire consulted the slow motion replay, the view of the crease was entirely obliterated by the square leg umpire’s posterior, which, given the fact that it belonged to David Shepherd, could not unreasonably be described as ample. Ergo, the first ever DRS referral in England, from just the one primitive camera, was a total balls up.

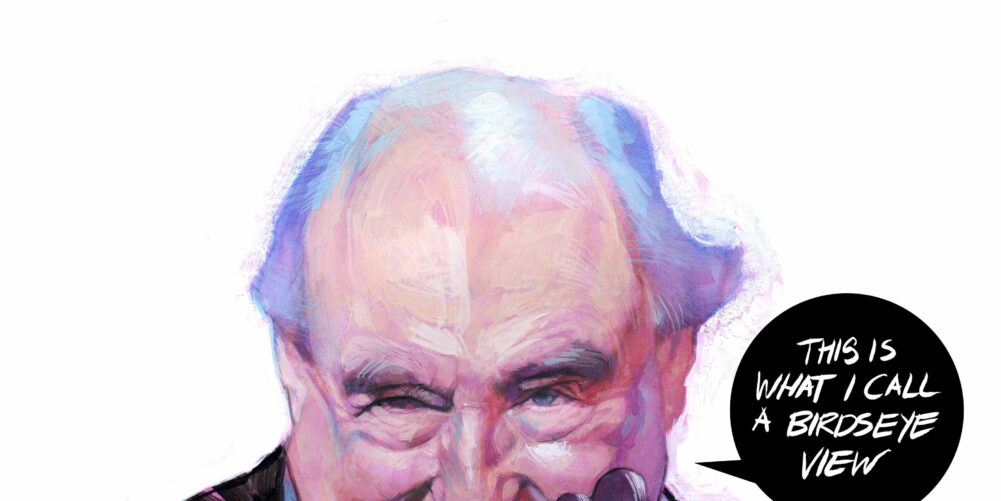

It’s all different now, with cameras not only all over the field but implanted in the stumps, and soon, I’ll wager, to be strapped to the umpire’s head, the spare helmet behind the wicketkeeper, the drinks trolley, and, pecking away in the outfield, one of Henry Blofeld’s pigeons. Giving a whole new meaning to a bird’s eye view.

Some would argue that cricket has lost some of his charm since DRS, and that one of the basic tenets of the game – the umpire’s decision is final – has been irrevocably lost. To be replaced, sometime in the not-too-distant future, by “the umpire’s decision is final. Just so long as it has first been referred to some bloke in front of a TV set, the House of Lords, and the European Court of Human Rights”.

Just imagine if WG Grace had referred the mysterious case of the fallen bail to the third umpire. Was it the wind, as the good doctor informed the umpire? Or was it a genuine case of clean bowled.

As great historical mysteries go, not quite in the same league as the Marie Celeste or Lord Lucan, but it would be nice to have had some hard evidence given WG’s reputation as a bit of a crook.

And therein lies a tale. Some people believe that DRS is the inevitable by-product of the noble game going down the same fraudulent path as football. Just as footballers have developed the canny knack of falling over for no apparent reason, so cricketers have morphed from scrupulously honest and upright citizens, to people who now practise their choirboy look in front of a mirror in the event of needing to convey innocence after a thick edge to the keeper.

However, it may actually be that DRS has actually brought a bit more honesty into the game, not so much a case of cricketers having had some kind of moral awakening as a practical re-appraisal. Closer – how can we put it? – to a loft conversion than a religious one.

Quite simply, a batsman will be more inclined to give himself out if he knows that the replay will come back showing a large glow on his outside edge, and revealing him, should he hang around waiting, to be a fraud. Needless to say, if the umpire’s finger remains in its holster, and the fielding side has run out of reviews, he’ll then come to a different conclusion. Namely that a licence to carry on batting is well worth it, if the only penalty is the barrage of sledging about to come his way.

The only real difference between not walking today, and not walking years ago, is that there used to be a stigma attached. Which I will illustrate with a story the former England off-spinner Jack Birkenshaw once told me, about a game at Leicester in the early Seventies when Ray Illingworth had Gloucestershire’s Arthur Milton caught off bat and pad shortly before lunch, but Arthur, a noted walker, never budged.

Over lunch, Milton’s batting partner said: “Bloody hell, Arthur, you hit that one,” and when a mortified Milton faced Illingworth again for the first ball after the interval, he ran down the pitch, deliberately missed it, and with a parting shout of “sorry lads!” kept on running towards the pavilion.

That kind of thing doesn’t happen today, but it would be a nonsense to say that English cricket was once a paragon of virtue. Denis Compton plastered his hair with Brylcreem because he got paid for it, but others doubtless used it for shining up the ball. And Ken Higgs, the old England seam bowler, could raise the seam with a one handed swivel from a left thumbnail so sharp he could have opened a can of baked beans with it.

We also tend to forget that there is one other reason why more batsmen walked in the old days, which is that there are no real rabbits any more.

Years ago, when the genuine No.11 had the end of his nose singed by a Colin Croft, or a Sylvester Clarke, he made an immediate beeline for the pavilion.

And if someone from the fielding side shouted: “Come back, you never hit it,” the reply was always the same. “Well it was close enough for me.”

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, Friday July 15 2016

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here