It was Pakistan’s parting shot, a swashbuckling T20 win over England that saw all their old characteristics of verve and swagger return, that brought up the old dichotomy of nature versus nurture and their respective merits.

To see England’s well-drilled cricketers outplayed totally with bat and ball was, for those of us who don’t believe sport should be bent to the will of data and algorithims, a heartening sight. For sheer flair and quick thinking on the hoof to triumph so overwhelmingly was gratifying.

Watching Sharjeel Khan cut, carve and pull the ball to all parts of Old Trafford was to marvel at a wonderfully natural talent. Sure, England’s bowlers appeared to have his number in the last two 50-over matches, but so fixated were they on a plan hatched in the dressing-room at Old Trafford, to bang the ball in short, that they forgot how they’d dominated him by bowling full and outside off-stump. Most disappointingly, they did not try to change on Wednesday night, retaining blind faith in a ploy that was obviously not working.

The natural talent versus the manufactured one has long been a talking point. In professional team sport, the former is often seen as possessing maverick tendencies which tend to pull against the greater good, though players can still be disciplined without being overly beholden to coaches. Yet, the talented maverick has always invited suspicion, their methods bordering on the reckless with he, or she, not having the team good at heart.

The relationship is probably a bit more complex than that, though interfering with natural talent nearly always requires great skill in itself. Get it right and consistency can follow. But get it wrong and calamity can ensue, as in the case of Alan Lilley, a teammate of mine at Essex.

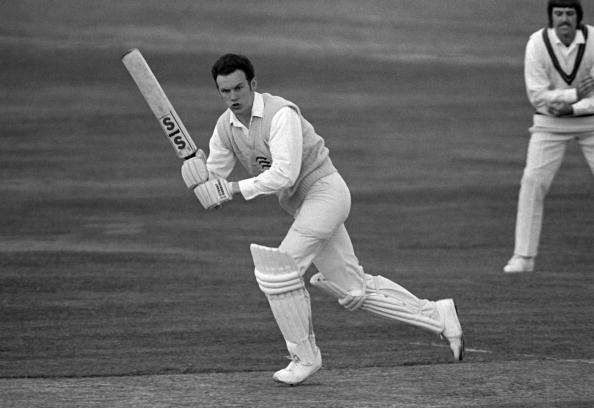

When I began with Essex Seconds in 1978, Lilley was the best batsman we had by a distance. Long before opening bowlers were belted back over their heads in white-ball cricket, Lilley would destroy attacks with his unfettered hitting in all formats. His refrain, when occasionally caught at long-off that, he was just pushing for one, was not an exaggeration.

I remember one match against Leicestershire Under-25s at Grace Road where Nick Cook, who’d just been among the wickets in the First XI, was taken apart by him.

Cook’s response was to thank god he was returning to first team duties the following day. At least the batsmen blocked it there.

In the last county game of that season against Nottinghamshire, Lilley made his first team debut and scored a hundred. But instead of letting him continue to ride the wave, Lilley was told that he wouldn’t be able to bat like that all the time as good bowlers would find him out. Now, while outside agencies are not entirely to blame for a career that foundered more or less from that point, they messed with an uninhibited talent and reduced it, mortally, in the process.

Free spirits should be encouraged providing they do not absolve themselves completely of responsibility towards the team, but it can be a difficult balance to strike.

Graham Gooch had a similar talent for hitting a cricket ball as Lilley, yet he did not trust it alone to lead him to greatness. That was where, ideologically at least, the ferment between him and David Gower began – Gower being a cavalier and improviser, relying on the situation to inspire him rather than any puritanical sense of duty to self or team. He was certainly not of the belief, as the author Malcolm Gladwell is, that 10,000 hours of practice will make you a world-class expert, something Gooch would probably find advocacy in.

Once coaches became a fixture in the late 1980s, Gooch placed a lot of faith in practice and training. He eschewed nets though, unlike Geoff Boycott, Nasser Hussain and Nick Compton, for whom the ‘practice makes perfect’ adage would drive teammates to distraction if there wasn’t a bowling machine around to give them their fix.

The free spirit versus the coached automaton may be the wrong way of looking at this dichotomy. Confidence, especially in one’s method and approach, is surely the most important factor. Although the occasional technical glitch might have been ironed out, Gooch’s increased work ethic was really just a way of bolstering his confidence that he’d done everything he could to prepare himself for the fray. It also meant that failure would not give him a guilty conscience. Gower’s way of coping did not require the same self-sacrifice.

Coaching is not entirely the devil’s spawn. It certainly has benefits among younger age groups, where delivering the basics can be key.

And yet what level of interference is desirable? Lasith Malinga is arguably the greatest death bowler there has aver been but his idiosyncratic, slinging action would not have got beyond infancy had he been coached as a youngster in England. The same with Muttiah Muralitharan, though some might argue, with the controversy over whether or not the bend in his arm was congenital, that might have been a good thing.

Coaches are certainly not all knowing, as shown by the famous occasion when Viv Richards and Andy Roberts – both up and coming Antiguan players at the time – visited Alf Gover’s famous indoor school in Wandsworth. The pronouncement, after each had been put through their paces, was that Roberts was a bit round-arm to make a good county bowler, while Richards played across the line too much. Thankfully, both ignored that snap assessment to become two of the greatest cricketers in history.

As cricket joins the world in seeking more control over its participants, and coaches proliferate as a result, individuality cannot help but to be compromised. It takes a wise coach with the lightest of touches to steer players towards finding their own solutions to problems, but that is a rare ideal.

Happily, minimal interference appears to be one that England’s coaches – Trevor Bayliss and Paul Farbrace – appear to advocate. Any more meddling risks producing a team of well-drilled, pre-programmed performers and that really won’t do.

For them and elsewhere, autonomy should be the goal, not automatons.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, September 9 2016

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here