Title drought could have ended had Edrich led throughout

Continuing our new series, cricket writer Paul Edwards looks back on the County Championship runners-up of 1956 and their understated and underrated batsman Geoff Edrich…

Unlike his brother, Bill, who played 39 times for England, or cousin John, who won 77 Test caps, Geoff Edrich never gained full international honours. The Commonwealth tour to India in 1953-4 was as near as he came and

few argued that Edrich’s pragmatic, back-foot batting style should earn him a place in England’s very strong top order during the early Fifties.

Yet to borrow EP Thompson’s phrase, Edrich, like so many players of his time, needs to be rescued from the “enormous condescension of posterity.” We note his 15,600 first-class runs, his 26 centuries and the eight seasons in which he scored over a thousand runs for Lancashire and conclude that here, to be sure, was a fine county batsman who helped his side win a share of the title with Surrey in 1950.

But unless you read the match reports and listen to the testimony of team mates, it is easy to overlook the widely-held belief that Edrich was also one of Lancashire’s bravest batsmen,

or the persuasive argument that had he been skipper throughout the 1956 season, the county’s wait for an outright County Championship win would have lasted a mere 22 years instead of 77.

And as we shall see, his courage and judgment came in many forms.

For it was faintly miraculous that Geoff Edrich ever played first-class cricket at all. Having made his Minor Counties debut at the age of 18 in 1937, he signed up for the Fifth Norfolk Regiment when war began and in

1941 he was posted to the Far East. He arrived in Malaya a month before the surrender to Japan and spent the next three and a half years as a prisoner.

For two years he was put to work on the “railroad of death” in Thailand and ended the war weighing six stone. Out of Edrich’s platoon of around 30 men, only half a dozen survived the war.

“I kept going with the help of one or two pals,” Edrich told Stephen Chalke in an interview which forms the basis for one of the chapters in the excellent A Long Half Hour. “You had to have a lot of luck – and one or two decent chaps with you. That’s probably what made me always feel that to have success at cricket, you’ve got to have team spirit, haven’t you?”

It may seem slightly odd to hear a cricketer link war and sport so easily but Edrich was not alone. Having served as a wartime pilot, the great Australian all-rounder, Keith Miller, was able to put any pressure that existed during a Test match in its proper context. When imprisoned in Singapore, Edrich and his comrades had played proper cricket matches.

It helped keep their morale up; it reminded them that wars end.

A few months after he returned home, Edrich found that Lancashire’s need for players was almost as great as his own for a county contract. He was one of seven cricketers awarded their caps in 1946 and scored 1,000 runs for the first time the following season.

He quickly became a fixture in the middle order, the sort of batsman who often scored his runs when they were most needed and the bowlers seemed in the ascendant. In August 1953 Edrich made 81 not out against Northants on a pig of a pitch. For much of that innings at Old Trafford he was facing Frank Tyson, arguably the fastest bowler England have ever produced. Early in his innings Edrich had his wrist broken by Tyson but he batted on to close of play and made 22 more runs the following morning. Lancashire lost the match by one wicket and Tyson described Lancashire’s second innings as “the closest I have ever come to killing a batsman”.

He quickly became a fixture in the middle order, the sort of batsman who often scored his runs when they were most needed and the bowlers seemed in the ascendant. In August 1953 Edrich made 81 not out against Northants on a pig of a pitch. For much of that innings at Old Trafford he was facing Frank Tyson, arguably the fastest bowler England have ever produced. Early in his innings Edrich had his wrist broken by Tyson but he batted on to close of play and made 22 more runs the following morning. Lancashire lost the match by one wicket and Tyson described Lancashire’s second innings as “the closest I have ever come to killing a batsman”.

“[Geoff] was the batsman to fight hardest of all against the odds,” said Edrich’s Australian team mate, Ken Grieves, another warrior-cricketer, “the one man who would never quit no matter how high the odds were stacked against him.”

By 1956 Lancashire had a team capable of challenging Surrey for the County Championship. Stuart Surridge’s multi-talented and superbly-led side had won the title in the four previous seasons but Lancashire had cricketers of undoubted quality, too. They included Brian Statham, whose fast bowling

partnership with Tyson had done so much to ensure England retained the Ashes in Australia two winters previously; there was Alan Wharton, who scored 1,389 runs in that wet summer; and there was Roy Tattersall, the seamer turned spinner whose accuracy and awkward pace made him one of the most respected bowlers on the circuit.

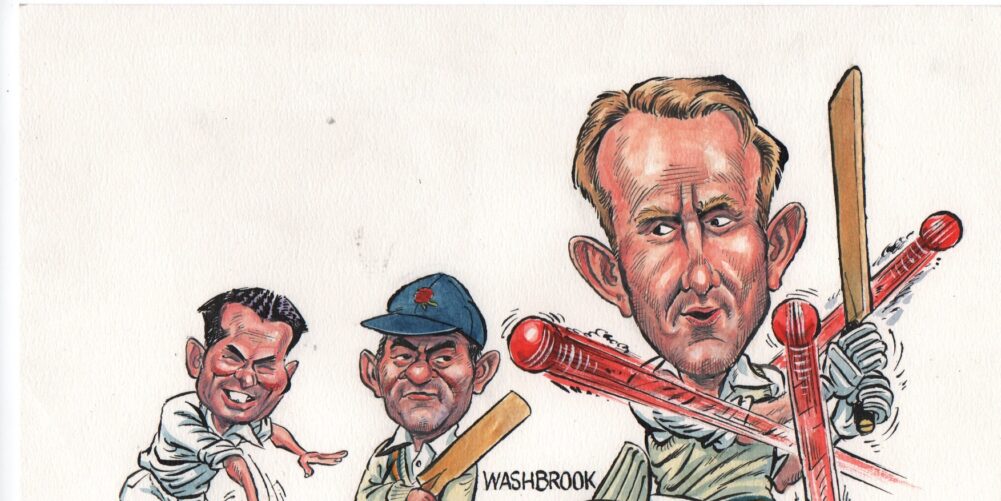

Entering his third season as captain of Lancashire in 1956 was 41-year-old Cyril Washbrook, a veteran of the side which had won the title in 1934 and one of England’s very best post-war batsmen. Indeed, so respected was Washbrook that he was drafted into the England side for the last three Ashes Tests of that damp summer and this, in addition to his duties as a selector, caused him to miss tenChampionship matches.

Geoff Edrich deputised for the captain and Lancashire were undefeated under his leadership. He even led Lancashire to victory over Leicestershire in a rain-affected two-day match in which the home side did not lose a wicket. The stand-in skipper declared his side’s first innings on 166-0 and trusted his bowlers to make the most of the conditions. Statham, who took seven wickets in the match, and slow left-armer Malcolm Hilton, who collected eight, did not let him down.

Lancashire lost only two Championship games in 1956 but they won three fewer games than Surrey and trailed the champions by 20 points in the final table. One of their defeats was at the hands of Kent at Canterbury and it was suffered towards the end of a seven-game spell in which Tattersall was left out of the side.

The omission of the bowler who had done as much as anyone to put his team in contention mystified Tattersall at the time and it mystified him still when I interviewed him three months before his death in 2011. The Manchester public were bemused, too. “Have you been a bad lad?” they asked this most mild-mannered of cricketers when they heard the news.

Papal elections were conducted with greater openness that some county selection meetings in that era but Washbrook never denied his part in Tattersall’s omission. But then Lancashire’s captain was a classic example of the outstanding Test cricketer ill-suited to the responsibility of captaincy, especially at the time of his appointment.

“Cyril was too stiff,” said Geoffrey Howard, Lancashire’s secretary throughout the Fifties. “He didn’t understand young people. He was one of those men, you can never imagine him every being a boy. [Geoff Edrich] always played to win. Cyril played not to lose. Geoff could have been a fine captain. He had a great feeling for the game and he understood the young players.”

Jack Bond, who skippered Lancashire to five one-day trophies, was even more forthcoming in his assessment of Edrich. “I spent a lot of time with Geoff,” he said. “He was like a father figure to me. A lot of things in my captaincy I learned from him. Cricket was his life. He’d eat, sleep and drink it.

“He has such a lot of knowledge. As a captain he was quite prepared to take a gamble. He backed his players on the field and in committee. Washbrook would let games drift, and that’s no good.”

There were revealing codas to that 1956 campaign. For the last game of the season, against Sussex at Hove, Washbrook had it in mind to make Edrich 12th man. “If you leave Geoff out, you’ll be left with ten because I won’t be playing,” said one player. Edrich made 102 to help Lancashire secure the runners-up spot.

Then, after Washbrook had made an off the cuff speech thanking the players, Malcolm Hilton chipped in: “Our skipper’s missed one person out. We’d all like to thank Geoff Edrich.”

Edrich’s playing involvement with Lancashire ended in 1959. He had been appointed second team captain two years previously and did the job supremely well until he refused to give Old Trafford officials the names of those players who had been involved in a minor late-night scrape in a Birmingham guest-house. He remained a players’ player to his marrow.

But Lancashire should have known better than to expect servility from Edrich. He had put a marker down in the late Forties when senior professional Dick Pollard had attempted to check the players’ appearance before they returned to their hotel after a Saturday night dance. Edrich informed him that he had been a prisoner of war for over three years and no one was going to tell him how to spend his evening. He had probably had enough of being lined up and ordered about.

After some low years – his war memories returned to plague him – Edrich was appointed groundsman and coach at Cheltenham College and spent the years until his retirement in that most tranquil of settings.

He did, however, attend a former players’ reunion at Old Trafford and was given a prolonged standing ovation by cricketers who remembered his contribution and knew a good man when they saw one.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, November 11 2016

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here