The local lads who delivered the county’s finest moment

Respected cricket writer Paul Edwards goes back 80 years to run the rule over Derbyshire’s solitary County Championship title

There is the past we remember, the past we ask others to recall and the past we can only read about.

Derbyshire’s single County Championship in 1936 is becoming securely ensconced in the third category. The number of people still alive who can claim to have watched Arthur Richardson’s great side win the title must be very few. Researchers can listen to old interviews with the players and they can read the books or delve in the primary sources; but the time when we can ask any of Richardson’s players what it was like to tweak the noses of mighty Yorkshire is long gone.

So this week’s County Archives does its best to commemorate the 80th anniversary of one of the finest yet least lauded triumphs in English domestic cricket. It was achieved by a side with a fair claim to be as home-grown as any of Yorkshire’s title-winners; a team containing Tommy Mitchell, one of the more complex characters to have played the game; and a side whose success was rather overlooked, even in its moment of glory.

Derbyshire, you see, were a fine team in the 1930s, but they were not a member of the ‘Big Six’. From 1890, when the title of Champion County acquired official status, until 1935, the title had been won in every season by one of Surrey, Yorkshire, Lancashire Middlesex, Kent or Nottinghamshire. Only Warwickshire in 1911 had disturbed the rough pattern.

In 1920 Derbyshire had recorded the worst results in the history of the championship – played 18, lost 17, abandoned 1 – but by the 1930s a side built by the diligence of the secretary, Will Taylor, and the shrewd judgement of the coach, Sam Cadman, was fit to be ranked with the best in the land. Under Guy Jackson, who captained Derbyshire for nine seasons until 1930, a bond was forged between an amateur skipper and the tough professionals. “I like that b**tard,” said Harry Storer, one of those tough pros and later manager of Derby County. “He hated losing.”

Jackson’s successor, Arthur Richardson, may not have been worth his place in the team as a batsman – 378 runs at an average of 12.6 is hardly evidence of indispensability – but he was a canny skipper and he had the respect of his players. Between 1934 and 1937 Derbyshire were never out of the top three in the final table. And it was vital that Richardson’s authority was accepted, for he had in his charge a team of professional men, many of whom had begun their working lives in coal mines or iron foundries. Most knew the value of their labour and very few blindly respected mere authority.

As John Shawcroft, the great historian of the county’s cricket, wrote: “For all the rugged grandeur of the Peak District and the beauty of the Dales, the cradles of Derbyshire cricket lay within the industrial belt, the lead mines of Wirksworth, the lace and train heritage of Derby, the pit hills, winding houses, smoke-misted sheds and fussy shunting engines of the coalfields.”

Shawcroft reckons that in the mid-1930s, a county professional earned on average £300 per annum whereas a coal face worker picked up £149. That made choosing the right skipper all the more important. Richardson’s players were not likely to let their chance of relative affluence be spoiled by some clueless prat accustomed only to ordering servants about.

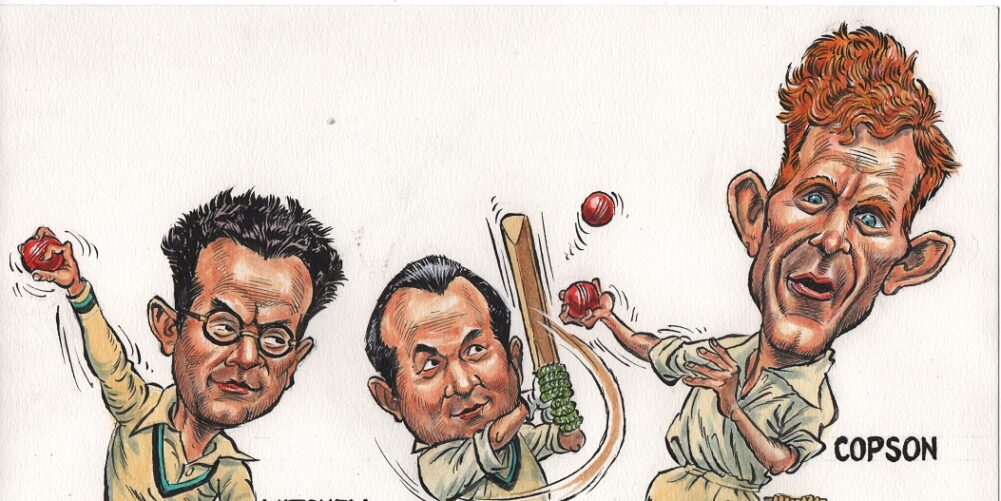

All the same, Tommy Mitchell would have presented a challenge to Mike Brearley in his pomp. Look at him in the 1936 team photograph and you might think he was a Cambridge mathematician, a cerebral type who would be found code-breaking at Bletchley Park when the second German unpleasantness began. You would be mistaken. The bespectacled Mitchell was a miner at Cresswell Colliery and, like the great seam bowler, Bill Copson, he was only recruited by Derbyshire when spotted playing improvised games during the 1926 General Strike. His ability to turn his leg-breaks and googlies was undoubted, however, and he quickly became one of the best exponents of his devilish arts.

Jovial when things were going well – the Who’s Who of Cricketers asserts he was known as “merry-hearted”, Mitchell was equally demonstrative when discontented with life. He was good enough to be picked for the 1932/33 Bodyline tour, but by 1936 his five-match Test career was over, partly because he bowled too many poor balls and partly because, in 1935, he had refused to bowl, telling the England captain, Bob Wyatt, that “he couldn’t captain a box of bloody lead soldiers”.

Under Richardson’s leadership, Mitchell took 116 wickets at 20.45 apiece in 1936, and he probably would have taken more had he not broken his thumb in the third last game of the season. His value was illustrated at Chelmsford on August 4, when Essex were 57 for three in their second innings and needed just 45 more on a good wicket. Then Mitchell, his shirt sleeves flapping around in typical fashion, took five for 25 in five overs. It was performances of that quality and eccentricity which appealed to RC Robertson-Glasgow and inspired one of the most brilliant of his Cricket Prints.

“If the cricketers of A.D. 2000 have any time to read of their forerunners, it is not likely that T. B. Mitchell, the little Derbyshire leg-break bowler, will long detain their interest or much excite their wonder,” it began. “Good enough, they will say, but not so good as so-and-so and so-and-so, and they will turn the page.

“[Mitchell is] a master of flight and variety [but] he only does it when he feels like it. He is not interested in a cold level of efficiency. He calls a spade a spade and something more, and I have often thought that he wouldn’t mind having a something-more spade to give a good wanging [correct, note to subs – Ed] to the pitch, or the umpire, or the batsman, or his own captain.”

“There is something of Donald Duck about him. No cricketer so conveys to the spectators the perplexities and frustration of man at the mercy of malignant fate. He has much in common with the golfer who missed short putts because of the uproar of butterflies in the adjoining meadow.”

But while the mercurial Mitchell was deadly on his day, the rather more equable Copson was an even more important member of Richardson’s attack. And together with Alf Pope, whose fast-medium bowling earned him 94 wickets in 1936, and Leslie Townsend, purveyor of quick off-breaks, the pair provided Richardson with maybe the best attack in the country.

Copson was a bowler of genuine pace. His 140 scalps included a dozen five-wicket returns, one of which was achieved against Surrey, when Derbyshire’s opponents had been 49 for two and needed just 45 more runs to win. Copson’s seven-over spell, in which he took six wickets for eight runs, decided the match.

Yet Copson was another cricketer who had benefited from Cadman’s coaching. After a childhood containing, in his mentor’s famous phrase, “more dinner times than dinners”, he had become a miner at Morton Colliery, where the 18-year-old’s ability to bowl fast and straight on the local recreation ground was noted. Copson was eventually signed by Derbyshire in 1931, and after spending the winter of 1935/36 training with Chesterfield FC, he was unusually fit and injury-free when the cricket season began. He was to spend the following winter touring Australia with Gubby Allen’s MCC team.

Copson was joined on that Ashes tour by Stan Worthington, one of four Derbyshire batsmen to score over 1,000 runs in 1936. This was a considerable achievement, not merely because the quartet played half their games on bowler-friendly home pitches, but also because it was a wet summer, the sort in which seamers make hay even when farmers can’t. So the achievement of Worthington, Denis Smith, Albert Alderman and the all-rounder Townsend was considerable although this did not stop bemused newspapers and magazines attempting to belittle it. “Paradoxical as it may appear,” bemused The Times, “it is Derbyshire’s relative weakness in batting which has contributed most to their success. Their scores have been low enough to give their bowlers a chance – and their bowlers have taken it.”

What was noticed by Wisden’s correspondent, however, was that Richardson’s batsmen had scored their runs quickly enough, when the situation demanded, to give Copson, Pope and Mitchell time to go to work. And in Harry Elliott Derbyshire they had one of the best wicketkeepers in the land. Like Mitchell, Copson and Worthington, Elliott played a handful of Test matches, but the impression remains that their county’s achievement in 1936 was underestimated and overlooked.

Asked now to name the three teams who have not won the title since 1890, relatively well-informed cricket supporters might still plump for Derbyshire as one of their selections. Maybe it is as well Tommy Mitchell isn’t around to put them right.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, December 9 2016

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here