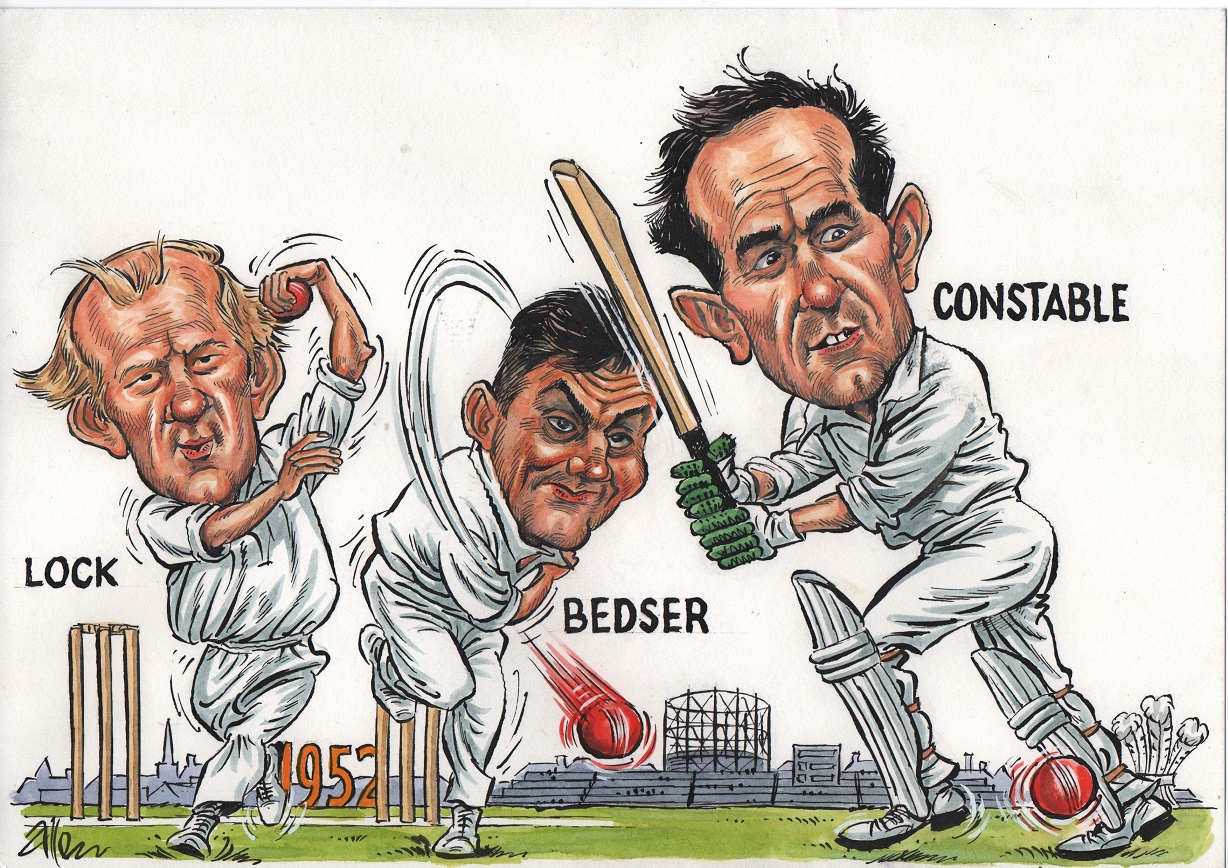

County Archives – Surrey 1952

The year when Bernie really shone among the stars…

Surrey had an army of leading lights in their 1952 title winning side, including the somewhat unheralded Bernie Constable, writes Paul Edwards

He was a small man among giants, a county cricketer who earned his place in a team which at times contained seven England players.

Surrey have won the Championship outright on 11 occasions since the war and he played in seven of those sides. His name was Bernie Constable.

Even at the Kia Oval, perhaps, relatively few people have heard of Constable these days and even fewer will have seen him play. The same goes for both the broad-shouldered opener, Tom Clark, who made over 1,000 runs for Surrey in the first three of their seven consecutive title-winning seasons, and for David Fletcher, who led the scoring in 1952 with 1,674 runs.

We should not be too surprised that memories fade a little. Twenty years after his retirement, Richie Benaud was asked by a young autograph-hunter who knew him only as a television commentator whether he had ever actually played cricket. Fortunately Benaud’s achievements do not need to be set out for readers of this column, but I have always reckoned there was something about Constable which merited further consideration. This, after all, is the man of whom the future England manager, Micky Stewart, said: “I learned more from Bernie than from anybody else in cricket”.

Constable was overshadowed by the charisma of his captain and the brilliance of his colleagues. He played under the inspirational leadership of Stuart Surridge, who skippered Surrey to five titles on the trot between 1952 and 1956. There were few bigger personalities in post-war county cricket than Surridge, whose treatment of his players could swing from the caustic to the comforting as required. “One reason for Surrey’s tremendous advance was the confident assurance of all the players,” said Wisden in its review of the 1952 season, “and for that happy frame of mind they had to thank Surridge.”

Rather more revealing, maybe, was the view of the former Essex batsman, Dickie Dodds: “At one time Surrey seemed to have eleven captains but this all ended abruptly when Stuart Surridge took over… He had a large frame, a large heart, he bowled large swingers and he cracked the whip… He led from the front and gave his orders, reprimands, encouragement and praise in language as spoken in the Borough Market.”

Surridge had almost an embarrassment of talent at his disposal: Alec Bedser was still at the peak of his powers in the early 50s and Surrey also boasted two spinners of the highest class in Jim Laker and Tony Lock. Despite Test calls, Bedser took 102 wickets in 1952 while Laker’s off-spin accounted for 86 and Lock’s slow left-armers another 116. There was little doubt which team possessed the best attack in the country and Surridge deployed his forces with ruthless enthusiasm.

Nowhere was this approach more obvious than in the fielding, which is so often the barometer of a proper team. Surrey’s close catching epitomised their cricket. Surridge himself took more catches (48) in 1952 than the wicketkeeper Arthur McIntyre (46) who, heaven help us, was no slouch. Lock bagged a further 37 catches and Jack Parker, 35.

“When we went out to field under Stuey,” said Stewart, who later became one of the very best close catchers in the game, “it was like going over the top out of the trenches. But he led by example. As a close fielder he set the standard for everybody. He’d stand there in the field bawling orders.”

Which is all very well if the tactics and psychology underpinning such bawling is as sound as it was in Surridge’s case. But the history of cricket is sadly blessed with amateur skippers whose knowledge was in inverse proportion to their certainty. Both Surridge and his successor, Peter May, were amateurs who knew the game and understood their players.

The standard set in 1952 was maintained for the next six summers. While there were more notable triumphs – Surrey were only eighth in the table five weeks from the end of a dank 1954 season – there was none more important than the first.

But where did Bernie Constable fit in to all this? Firstly, as a batsman, of course. Neat, stylish and capable of scoring runs all round the wicket, he went in first wicket down for Surrey and retained his place in the top five even when the county’s batting had been greatly strengthened by the emergence of Ken Barrington and Micky Stewart, and the increased availability of Peter May.

To overpraise Constable’s batting is to do him a disservice. For example, once the Cambridge term had ended in 1952, May pummelled 804 runs in 14 innings at an average of 67, nearly 30 runs higher than Constable, who missed just three of Surrey’s 28 County Championship games that season.

Yet there was more to Constable’s cricket than that. For one thing, he was an excellent cover-point, someone whose outfielding offered an example to his colleagues. It was an asset which the astute Sturridge appreciated.

“He [Constable] knew exactly where to position himself,” said the skipper. “He had studied batsmen and knew their strokes so that he positioned himself at just the spot where he knew that they would hit the ball. He was a marvellous fielder.”

Surridge’s comment is even more enlightening when we realise that Constable frequently disagreed with his captain’s field-placings and expressed his views quite openly on the field. That the Surrey skipper could tolerate such dissent reflected his understanding of the player and the strength of his own position. He knew that Constable’s views were to be respected even if he did not agree with them; and he understood that such discussions did not diminish his own authority.

Constable’s knowledge of the game was also noticed by the future Surrey skipper, Micky Stewart. “Bernie used to watch like a hawk when new players came in,” he said “Even the way they were holding their bat when they came out of the pavilion. They’d take guard, and he’d come in from cover, till he was only three or four yards away, looking at the way they were holding the bat. Staring.”

Bernie Constable never held any official position at Surrey; as a professional, it would have been exceptionally difficult for him to do so. Yet he was an influence, whether by berating young batsmen for having given their wicket away when well set or by exhorting his colleagues to greater effort. One example serves to make the point. In 1954 Surrey took the title by winning nine of their last ten matches. Early in that run they played Northamptonshire at Kettering. It was a low-scoring game and one dominated by spinners. When the ninth Surrey batsman was dismissed, seven runs were needed to win and the home attack included Frank Tyson, the fastest bowler in the world. The visitors’ No.11 was Peter Loader, a fine seam bowler but rarely noted for displaying courage in the face of extreme pace.

Let us allow Stephen Chalke to take up the story…

“As Loader emerged from the pavilion his path was blocked by an animated Bernie Constable, who had earlier taken a few body blows from Tyson and was now waving his bat about and gesticulating repeatedly. ‘What was all that about?’ the others asked when Constable returned to the dressing room. ‘I told him if he takes one step to leg, he’ll have this bloody bat round his head when he gets back. And it will hurt a lot more than a cricket ball.’ ”

Clearly it little mattered that Constable himself had made a total of 19 runs in the match and had been run out for 12 in the second innings. He was confident enough – something of the Surrey strut, perhaps? – to make it clear to Loader what was expected of him.

Bernie Constable made his Championship debut against Lancashire in 1939. He batted at 10, contributed six in his only innings and caught a catch off the skipper, Monty Garland-Wells. The last day of the game was abandoned because Germany had invaded Poland.

When Constable retired, a quarter of a century later, he had made 18,849 first-class runs. His benefit in 1959 raised £6,515, not bad at all in those days for this son of boat-builders in East Molesey, who returned to joinery and shop-fitting when his cricketing days were done.

But his heyday was the 1950s, a simple decade of modest affluence for most folk, one in which Dixon of Dock Green was on the telly, a bobby was on the beat and a Constable was batting for Surrey. Peter May described him as “one of those unspectacular players on whom most sides rely more than is usually recognised.” The assessment is fair.

Constable probably had little doubt of his value to Surrey and he clearly had few illusions that, for example, his tenacity in batting on uncovered pitches would be remembered for long.

“In years to come, when they talk about this Surrey team, it will be all about the bowlers and about Peter May,” he said. “There won’t be one mention of the rest of us poor buggers who’ve had to bat on these bloody pitches.”

So perhaps one may be allowed the slightest frisson of satisfaction that this week’s County Archive proves Constable wrong, for once. Almost 20 years after his passing, the little man has another day in the sun.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, February 3 2017

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here