Derek Pringle column – Capturing the soul of cricket and its legends

Has there been a game or sport more celebrated by art than cricket? From the 17th century country house artists painting the lord of the manor’s team to the bold commissions of the game’s great players by the MCC, art has served cricket, and vice versa, since its origins on the uplands of southern England 350 years ago.

Cricket’s inspiration to poets and writers is well known, but it has also stirred the creative juices of artists in the unlikeliest of ways. In 2008, Tate Britain presented an exhibition of the works of Francis Bacon. For those readers unfamiliar with Bacon’s work, there is a brooding menace to most of his paintings depicting, as they do, debased and distorted images of the human body and condition.

Bright colours are often used, mostly for the background, but there is nothing sunny about these paintings which ooze pain. While most of the finished paintings were unsettling, the Tate had several glass cases filled with images that had inspired Bacon, often ripped from magazines and newspapers.

Among them were some cricket action photos: Alan Knott appealing for an lbw and another of Bhagwat Chandrasekhar bowling.

Cricket obviously fascinated him and while neither of these works were in the Tate exhibition, Bacon painted both a triptych and a diptych between 1982-1984 where one of the panels in each depicted a figure wearing cricket pads.

In the diptych, entitled Study Of The Human Body – From A Drawing By Ingres, the figure is painted adopting a wicket-keeper’s pose behind the stumps though he is without head, gloves or clothes, and his shoes don’t match. Squatting on a table with a bright acid orange backdrop, it is a highly sexualised image, its primeval rawness at odds with cricket’s stylised rituals and politesse.

Peter Doig, another artist not overtly associated with cricket despite being taught art by an MCC member, has also created a cricket painting with a similar orange backdrop. His work actually depicts a game of windball on a Trinidadian beach and is called Cricket Painting (Paragrand), after the beach on which the game is played.

A Scot, Doig recently held the record for the largest sum achieved for a work by a living European artist when his paintings, The White Canoe and The Architect’s House In The Ravine, sold for about £6m and £7.7m respectively.

That success has put Doig beyond even the MCC’s purse for a commission but the club is gradually assembling a superb body of contemporary art celebrating cricket to go with the decorative British art in its collection from earlier centuries.

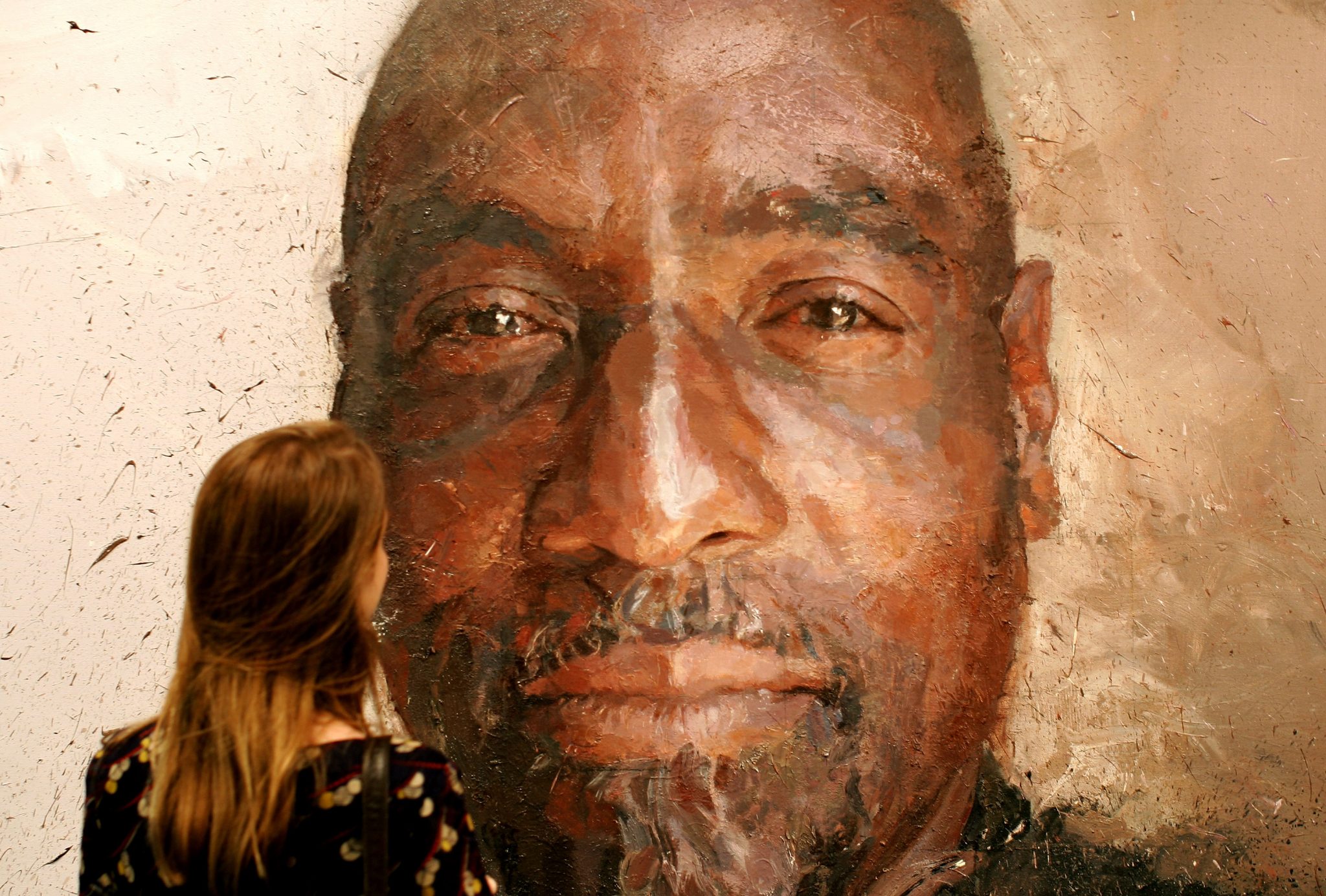

Hung all over Lord’s pavilion and in the museum, the recent commissions depict mainly England captains along with their counterparts from other countries, as well as leading modern cricketers like Glenn McGrath and Shane Warne. The best of them excite as much as the finest innings and bowling performances on the baize outside. My own favourites are Brendan Kelly’s portrait of Vivian Richards, Justin Mortimer’s painting of McGrath and Stuart Pearson Wright’s depiction of those great Indian cricketers, Kapil Dev, Bishan Bedi and Dilip Vengsarkar.

The painting of Viv is huge and, although it depicts him well into retirement, it captures all of the fire and ire that drove him throughout his playing career. I don’t know what MCC members make of this huge canvas as it peers down at them but for me it exudes menace.

I have looked into those eyes in the middle (not for too long mind as they’d have the opposite effect of Medusa and turn bowlers to jelly rather than stone), and the intimidation in the painting feels very real and, while you remain in its presence, inescapable.

With no background scene to distract, it is all about Viv, the paint thick and the strokes, like those of its subject in his pomp, muscular. But there are also flicks and flecks of paint flying off Viv’s face which suggest a disintegrating supernova. According to the artist, these were created by attaching a brush loaded with paint to the end of a high speed drill and were done to depict the explosive energy Viv imparted whenever he attacked a cricket ball. Whatever the genesis of the idea, it contributes to an incredible painting.

The one of McGrath, done by Justin Mortimer, is more about McGrath the man rather than the cricketer, despite him wearing whites and the Baggy Green. Hemmed in by a dark field of background paint, it shows the fast bowler at repose, his bowling arm lolling by his side as if contemplating the hand life had dealt him by that late stage of his career – fame and plaudits as one of Australia’s greatest ever bowlers, but with his wife, Jane, terminally ill with breast cancer. Poignant in a way the game itself can never match.

More than just about any player I have come across, McGrath was prone to white-line fever, a condition where players assume a very different personality once they cross the boundary rope on to the field of play. A snarling sledger with ball in hand, McGrath was unfailingly polite, thoughtful and a little bit shy in “civilian life”, a side the artist has caught beautifully here.

The paintings of Bedi, Kapil and Vengsarkar are almost cartoonish in their imagery yet there is no mistaking who they are. Unlike the previous portraits discussed, here the backdrop impacts heavily on the overall feel.

Artists hate being compared to others but there is no escaping the impression that with the flat, brightly lit and coloured backscapes of grounds, outfields and stands, and in the heavy shadows cast by both the subjects and the stumps, it recalls the surrealism of De Chirico and Salvador Dali. But then Indian cricket, with its tricky spinners and wristy batsmen, has always assumed a mysterious air that is the hallmark of those two painters.

There are other analogues and in a throwback to those posed Edwardian photographs of players like Gilbert Jessop and Victor Trumper, usually taken on the Lord’s Nursery, Vengsarkar is depicted wearing black shoes.

As Vengsarkar had retired by the time of the commission, perhaps that is what he wore when posing for the portrait, the artist believing, as Bacon did, that messing with the shoes messes with convention in all kinds of ways that is not cricket. But then that is exactly what great art, and not just that which reflects cricket, is meant to do.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, February 3 2017

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here