There was a time when an England fielder’s method of preventing an extra run involved nothing much more strenuous than an arthritic stoop, or – for those who considered that bending over was way above the call of duty – a half-hearted attempt at an interception with the toe of the boot.

These days, however, the effort expended in preventing the addition of an extra run to the opposition total is liable to result in the kind of carnage that leads to serious news bulletins. Ending with the stern message that hopes of finding survivors among the wreckage – such as a trampled steward, or a boundary rope cameraman last seen flying through the air clutching a telescopic lens – were “fading fast”.

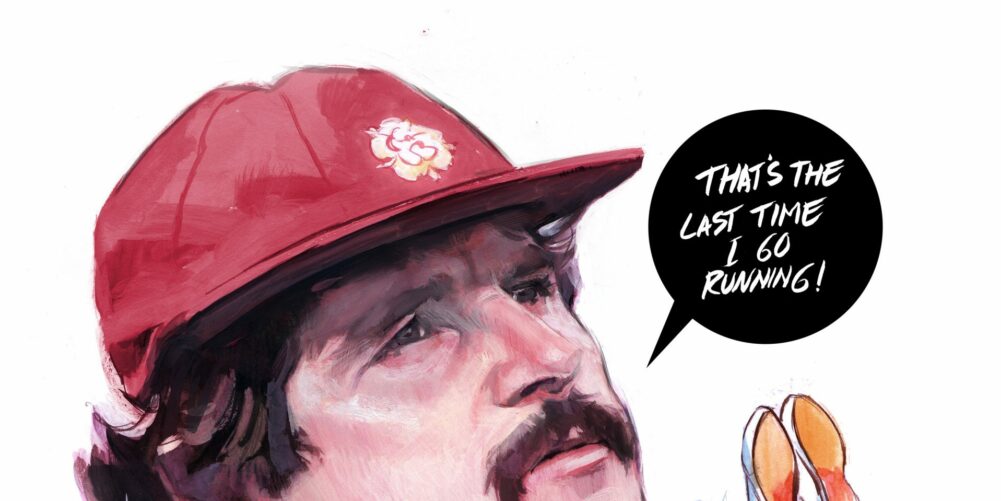

Tuning into the evening news, the viewer is confronted what appears to be a visit from one of those freak weather events now invested with names, like Hurricane Henry, or Tornado Teresa. In which case, keep an eye out this summer for Storm Ben, named after the England all-rounder who doesn’t slow down in his bid to intercept a cricket ball heading for the boundary even if his momentum takes him up the pavilion steps, past the members’ bar and into the car park.

Notwithstanding the fact that the opposition requires 400 to win with two balls remaining.

However, while Stokes is the best example of someone who would happily lay down his life this summer to ensure that AB de Villiers only moves from 11 to 14 rather than 11 to 15, the principle applies to nearly all international cricketers nowadays. The cost of a Test match ticket may make your eyes water, but let’s face it. How else are they going to pay for all those laundry bills?

I tried to conjure up a vision of Colin Cowdrey and Colin Milburn setting off as a relay team, as is the modern way, to turn a four into a three, but the imagination can only stretch so far. Similarly, Inzamam-ul-Haq doing one of these “beep” tests. Inzy was only once known to break sweat during his illustrious career, and that was when he waded into the crowd to take issue with someone who kept calling him a potato.

I’m not entirely sure who was initially responsible for the modern focus on physical fitness, but high on the list of suspects would have to be Graham Gooch. Naturally inclined to put on the odd pound if he wasn’t careful, Gooch took steps to make sure that this wouldn’t happen. And when I say steps, I mean literally.

Anyone who’s toured India will know that getting into a hotel lift without carrying a set of rosary beads and enough food and drink to last you a fortnight is a pretty bad idea, and my own method of avoiding the lengthy incarceration that followed a power cut was to take the fire escape.

And it was while descending down the concrete steps to the lobby that I invariably bumped into the-then England skipper, pounding up and down in his gym gear, and spraying you with sweat as he passed. Dear old Goochie. He even spread the fitness gospel to his team-mates, and on one England tour to Australia, he organised a group run from the ground in Ballarat back to the hotel. Which resulted in Allan Lamb making the second half of the journey in a taxi, having pulled a calf muscle en route.

Nutrition has changed a bit, too. I’m not sure what the likes of Stokes, Alastair Cook, Joe Root, and Jonny Bairstow ingest on match days, but I’m guessing it’s not quite how it used to be a few decades ago, when a professional cricketer’s food intake over a 24-hour period would have represented a major blow-out even for a blue whale. A creature, I was reading just the other day, which has a daily calorie intake equivalent to 6,000 Snickers bars.

First, there was the hotel breakfast fry-up, followed by tea and chocolate biscuits just before taking the field. After which, a couple of hours standing at slip would leave a chap ravenous enough to devour a bowl of soup, a bread roll, a main course of meat, roast potatoes and three veg, followed by spotted dick and custard, and cheese and biscuits.

This just about got you through to tea, where 20 minutes gave you barely enough time to devour half a dozen sandwiches, a couple of cream scones, and a slice of chocolate cake. And, after play was done for the day, it was nine pints of Old Dogbolter and an enormous curry to get you through the night and through to the fried bread and sausage.

No self-respecting bowler, for example, would turn up for a new season anything less than a stone overweight, which he’d then shed with three weeks of net bowling.

And he’s stay fit for the rest of the summer by bowling, bowling, and bowling. Like Fred Trueman, whose first encounter with a prospective fitness regime almost resulted in him biting clean through the stem of his pipe.

It was on the-then traditional boat trip to Australia, for the Ashes tour of 1962-63, when the Olympic athlete Gordon Pirie was co-opted as the team’s shipboard fitness coach.

Pirie informed Fred that he had a formula for strengthening his legs, to which Trueman replied that a thousand overs the previous summer (it was actually 1,141) had already done the trick, and that he had his own fitness plan for Pirie, which involved chucking him overboard, and seeing whether Pirie’s own legs – which Trueman sarcastically compared to the common house sparrow’s – might benefit from a spot of ocean swimming.

Andrew Flintoff, Shane Warne, and Mike Gatting somehow managed to carve out modestly successful careers without being required to lift anything much heavier than a knife and fork. However, the way cricket is going we may have said goodbye to some priceless repartee, of the sort heard on the 1984-5 tour to India, when the captain, David Gower, consulted the bowler, Chris Cowdrey, about a potential change in the field. “Hey Chris!” shouted Gower. “Would you like Gatt a bit wider?” To which Cowdrey replied: “No thanks. If Gatt got any wider he’d burst.”

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, February 3 2017

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here