Russell’s one-day kings who took no prisoners

While a Championship continues to elude them, no team could touch Gloucestershire at the turn of the century in limited-overs cricket, writes Paul Edwards

In another life, one that now seems both distant and close as Brideshead, I was a teacher at a lovely school in the Cotswolds. Part of my duties involved cricket, and it was this which brought me into contact with the man from whom I learned more about the game than anybody else.

David Essenhigh was an all-rounder who played cricket as often as his duties as a groundsman would allow, but his abiding love was coaching. One evening we were discussing a teenager David had seen play and whom he also knew through his friendship with the county coach, Graham Wiltshire.

“This lad’s got it,” said Essy, his eyes blazing with certainty and delight.

“But how do you know?” I asked. “Is it his talent, his cricket intelligence or what?”

“It’s both of them,” came the reply. “But more than those things, the lad’s got it here!” And he jabbed a finger at the centre of his torso. He was pointing to his guts. The young cricketer’s name was Jack Russell.

I thought of that conversation as I watched Russell make his maiden first-class century in an Ashes Test match at Old Trafford, and then again during the Siege of Johannesburg in 1995 when he and Michael Atherton defied all that the South African attack could hurl at them. Then there was his wicketkeeping: neat, precise, quiet. Many writers drew attention to Russell’s battered sunhat, his taped-up pads and his sunglasses, but most also conceded that whatever his eccentricities might be, he also happened to be the finest keeper in the country.

“Russell was the best wicketkeeper I ever bowled to,” said Angus Fraser, “He had these lovely soft hands, which enveloped the ball. It was like bowling into a big cushion, or a sponge that absorbed everything. He changed the game too… by standing up to the medium- pacers and controlling the game from there.”

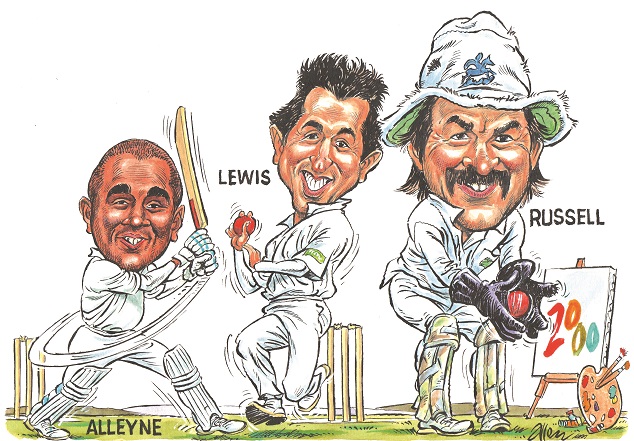

Stroud-born Russell was also one of those cricketers whom you could not imagine playing for any other county than that in which they were raised. His loyalties to Gloucestershire and England were formed early and went very deep. So it was a particular pleasure to see him play a vital role in the greatest era of his county’s recent history, one in which Gloucestershire won five limited-overs trophies in two seasons and became, beyond serious dispute, the best one-day side in the country. Winning the County Championship remains an unfulfilled ambition for Gloucestershire’s players and supporters; six runners-up spots is the best they have managed. But many neutrals were still delighted for the cricket-lovers who pack the College Ground during the Cheltenham Festival when, at the turn of this century, Mark Alleyne’s side ruled the short-form game. In 2000 they completed a clean sweep, winning the NatWest Trophy, the Benson and Hedges Cup and the Norwich Union National League.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Gloucestershire in those years was that while counties were regularly recruiting high-profile Test cricketers, they were content to replace the great West Indian fast bowler Courtney Walsh with the all-rounder, Ian Harvey, whose appearances for his native Australia were confined to 73 One-Day Internationals, in none of which he made a fifty or took five wickets. But individual stardom was never a terribly powerful selling point for Gloucestershire in that new era; their coach, John Bracewell, who had been appointed in 1998, replaced the fastest gun in the West Country with a bowler whose variations made him equally feared at the business end of one-day innings. “Few imports have ever been so influential,” wrote David Foot in the 2004 Wisden.

Yet while Harvey was a resourceful batsman, a brilliant fielder and a medium-pace bowler whose bottomless bag of deceptions – slower ball, bouncer, yorker – made batsmen look daft as well as incompetent, he was only one element in a side which always amounted to more than the total of its individual talents. Almost every cricketer talks about the importance of team work and collective effort, but few sides make these virtues into articles of faith in quite the fashion Gloucestershire managed in 2000. And fielding, Jack Russell believes, was the beating heart of it all.

“John Bracewell came in and opened our eyes,” he said. “In a couple of seasons he made us into a very fit team. People like Kim Barnett and Jeremy Snape arrived and we knew that if we stuck to our thing, we would be very difficult to beat. Two years previously we had decided we wanted to be the Manchester United of one-day cricket. Bracewell used to crack the whip, while Alleyne was more laidback, although he had a ruthless edge to him. The combination worked well. Fielding came first in our meetings because we knew that if we fielded to the best of our ability, the batting and bowling would take care of themselves.”

Bristol’s Nevil Road ground became a mighty redoubt and rarely more so than in the two semi-finals against Lancashire in 2000. In the B&H game, Rob Cunliffe turned up to watch the cricket but was drafted in to replace Harvey, who had pulled a hamstring. Cunliffe made 71, the seamers, Mike Smith and Jon Lewis, took six wickets and Gloucestershire won by 15 runs. Harvey’s five-fer, followed by Tim Hancock and Matt Windows’ half-centuries, helped Gloucestershire beat Glamorgan by seven wickets in the final.

But perhaps it is a direct comparison of the two sides in that semi-final at Bristol which is the most illuminating aspect of the affair: Lancashire had Atherton, John Crawley, Andrew Flintoff, Neil Fairbrother; Gloucestershire had Hancock, Kim Barnett, Windows and Chris Taylor. But the home side knew their own slow, low wicket and they were sustained by a self-belief born of thorough preparation.

“Opponents walked through the gate at Bristol with a resigned look on their faces because they knew they wouldn’t beat us on those pitches with our two spinners,” said Russell. “Nobody enjoyed playing limited-overs matches against us. We knew we would win if we did our basics.

“We warmed up like jets and the intensity of our fielding practice on the day before games was such that we could take that into the matches themselves. The only time we became complacent was in 2001 when we thought we’d cracked it and we won sod all.”

There was little sign of any carelessness from Gloucestershire’s cricketers in 2000. For August’s NatWest Trophy semi-final Lancashire strengthened their side with Sourav Ganguly, while Bracewell merely opted for Martyn Ball’s off-spin ahead of Cunliffe’s batting. The margin this time was 98 runs and Alleyne’s men went on to beat Warwickshire by 22 runs in a damp showpiece at Lord’s. Gloucestershire had won four finals on the trot; it was stump-grabbing time again.

The last of these triumphs was perhaps the oddest because Alleyne’s team became one of the few in the history of cricket to win a knockout competition after losing a match. Their three-wicket defeat to Worcestershire in June had seemed to have ended their chances until it was discovered that the victors had included the ineligible Kabir Ali in their side. Even in the replay ordered by the ECB, Worcestershire’s last pair needed six runs off the last two overs before Harvey sent down a maiden to Glenn McGrath and Ball bowled Steve Rhodes.

On the next day Gloucestershire travelled to Grace Road where Leicestershire needed 20 off 30 balls with five wickets in hand, but lost by ten runs – James Averis taking two of the wickets. These were seasons in which Gloucestershire knew how to win limited-overs matches and retained a justified confidence that they would somehow find a way to do so.

“It was just a magic time,” said Russell, “You could have been the richest bloke on the planet – Bill Gates or John Paul Getty – and you couldn’t buy it. Everyone was good at their job and nobody wanted to let anybody down. If you gave away two runs at fine leg, there was hell on earth. We just knew how to squeeze people but it didn’t happen by chance, it took a lot of hard work. We honestly thought we’d beat England in a one-day game.”

Limited-overs success took its time to feed into Gloucestershire’s Championship cricket in 2000 and even then it did not do so fully. Five wins in their last six games left Alleyne’s team in fourth place in Division Two and two points short of achieving promotion in a three-up, three-down season. That was hard on Lewis, who took 56 wickets in 14 matches, but the fact that Windows’ 790 runs made him the leading scorer told its own story, one that did nothing to detract from the glory of the other narratives.

Jack Russell is now a successful painter; he has replaced one art with another. His gazebo is a familiar sight at outgrounds around the country. As for Gloucestershire, their triumph over Surrey in the 2015 Royal London One-Day Cup was a reminder that they retain the ability to whip chairs away from the bottoms of the mighty.

Supporters in the Cotswolds comfort themselves with the notion that a first County Championship is more than a winter daydream.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, February 10 2017

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here