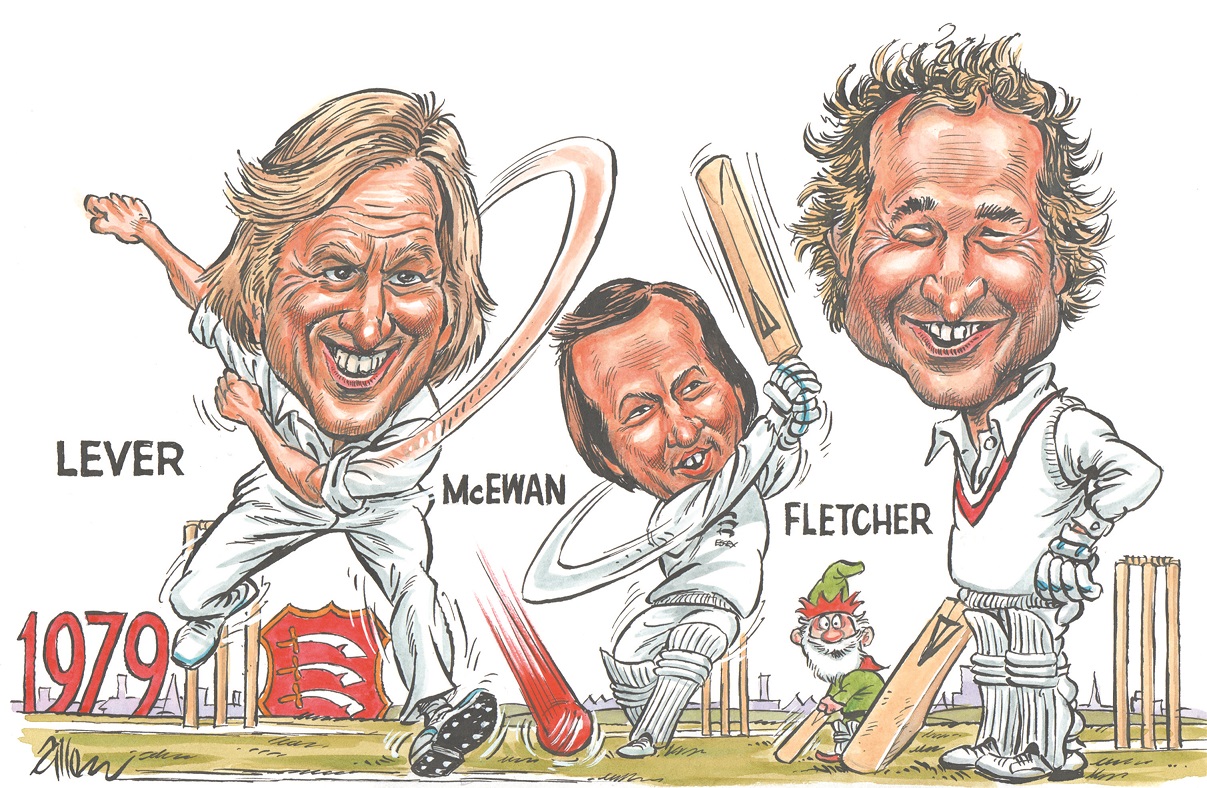

County Archives – Essex 1979

Champions who smiled their way to the title

Paul Edwards continues his fascinating series on the county teams by looking at how perennial also-rans Essex suddenly found a devastating combination

For much of the 20th century cricketers enjoyed playing against Essex and their reasons for doing so are not hard to discern. For one thing, there was a fair chance they would win the game; in the 73 seasons following their admission to the Championship in 1895, Essex finished in the top three only once. While no team including players such as Morris Nichols or Trevor Bailey could be considered an easy touch, the prospect of meeting Essex still offered their opponents reasonable hope of success, something which could not always be said of nearby Middlesex or Surrey.

But there were other reasons why players looked forward to visiting Ilford or Colchester. Matches on those outgrounds were generally played in a good spirit and it seemed certain that a three-day trip would be filled with laughter and fun. Essex may have been cash-poor but they were the most homely of the Home Counties. Playing at Lord’s or the Oval was a great experience but it was also rather like visiting a stern old aunt; you had to be careful not to knock over priceless ornaments or break wind during meals. Against Essex you could kick off your shoes, open a bottle and chew the fat.

Maybe Essex’s itinerancy had something to do with it. Until they bought Chelmsford and built a pavilion there in 1966 -– and even that was only made possible because Warwickshire’s Supporters Association gave them an interest-free loan – the county did not own a ground. Instead they were blessed with having to travel round their deceptively large county, throwing up marquees and setting up caravans in as many as seven venues each year. Perhaps it is difficult to be glum when you bring all the fun of the fair with you.

Yet the great thing with Essex was that when success arrived in 1979, it did not spoil them. Inspired at first by the gruff-kind leadership of Brian ‘Tonker’ Taylor, the players had welcomed the introduction of the John Player League in 1969 and performed well in it. Essex’s officials were deeply grateful for the increased income 40-over Sunday cricket provided and by the mid-1970s the county had assembled a squad of fine players, many of whom were reaching the peak of their powers.

The most abundantly talented of the younger generation was Graham Gooch, who made his county debut in 1973, but when Essex finished second to Kent in the 1978 County Championship, Gooch’s England commitments resulted in him playing just over half his county’s games.

However, the skipper Keith Fletcher, Ken McEwan and Brian Hardie all scored over a thousand runs while John Lever and Ray East took in excess of 90 wickets. A familiar pattern had been set and it was one shared by almost all successful county sides of whatever era. Nigel Fuller summed it up in the 1980 Wisden: “Loss of form or the absence of key players was barely detectable, for others would strike a vein of form and provide rewarding compensation.”

The personnel gradually changed at Chelmsford over the next 14 summers but the ethos inculcated by Taylor, Fletcher and, later, Gooch, remained remarkably unchanged. In their great era Essex won six County Championships and five one-day trophies. By the time the last of the titles was won only Gooch remained from the team which had secured the first, in 1979.

That dam-busting trophy was won with the help of Lever, the best left-arm seamer of his generation, McEwan, a batsman who could not have bought more enthusiastically into the Essex approach had he been born in Billericay instead of Bedford, South Africa, and Fletcher, a captain many still regard as the shrewdest they played with or against.

Perhaps it needed a player from overseas to appreciate the Essex approach. Certainly the county was fortunate in its recruitment of McEwan, whose classical batting earned him 18,088 runs over 12 seasons and the deep affection of many at Chelmsford. The South African’s style – and something of that affection – was captured by David Lemmon:

“Once, while making a century against Kent in Tunbridge Wells, Ken McEwan straight drove, square cut and pulled Derek Underwood to the boundary in the space of one over. Each shot was executed with regal charm, and never a hint of arrogance. He batted, as did the ancients, upright, correct and magisterial. He was incapable of profaning the art of batting, incapable of an ineloquent gesture.”

McEwan’s own feelings towards the county where he stayed for a dozen summers were expressed in humbler but no less revealing words: “At pre-season practice we had to put up the nets ourselves and, if somebody was moving some chairs, we had to go and help them. It was a lovely atmosphere. Every day I had a good laugh. I felt very at home.”

The South African’s pleasure was shared by Essex supporters in the first half of the 1979 season. In his first 13 innings McEwan scored 836 runs, milking the Warwickshire attack for a graceful double-hundred at Edgbaston and taking a mere 185 off the Derbyshire bowlers at Chelmsford. Both performances were incorporated into innings victories for Essex; for like all successful captains, Fletcher saw little point in individual achievement if it could not play a part in collective success.

After a dip in form, McEwan scored a century against Yorkshire in the final match of the season, a game Essex lost by one wicket, but by then the county’s first title had long been secured. It had been won with four matches to spare and with the assertion of an undoubted dominance which Essex’s opponents at Scarborough probably appreciated. Fletcher’s team won 13 of their 21 games in 1979; runners-up Worcestershire managed seven victories and finished 77 points behind the new champions, a greater margin than that which separated the New Road team from 15th-placed Warwickshire.

Essex’s batting may have been dominated by McEwan in the early months of 1979 but it did not revolve around him. Hardie, Stenhousemuir’s finest, also contributed three centuries and Mike Denness, the other Scot in the top order, added two more. When runs were needed from the middle-order, Stuart Turner often provided them. This most popular and committed of all-rounders marked his benefit year by making 525 runs and taking 57 wickets; a veteran of both near-misses and one or two mediocre seasons, Turner savoured the title as deeply as anyone.

The spin bowling of David Acfield and East played a less significant part in Essex winning the title in 1979 than in drier summers but the off-spinner Acfield still took five wickets in three successive matches in July, all of which Essex won, and he and East shared all ten when Nottinghamshire collapsed from 87-1 to 123 all out when needing only 170 to win at Southend.

East, meanwhile maintained his reputation as one of county cricket’s incurable comedians, although the more cerebral Acfield’s observation that “we didn’t take ourselves too seriously but we took the game seriously” probably puts Essex’s joyous cricket in its proper perspective.

And yet, when Essex supporters recall that summer of their first Championship, the cricketer that comes to their minds may not be the stylish McEwan or the canny Fletcher, albeit that the former charmed the crowds and the latter devised stratagems of victory. Nor might they immediately remember the reliable seam bowling of Norbert Phillip or the fine wicketkeeping of Neil Smith.

Instead, they will recall a six-foot tall, blonde-haired, left-arm seamer, whose ability to swing a cricket ball later than seemed decent was too much for all but the most skilful batsmen in the land.

John Lever (JK to everyone in the game) was to enjoy more successful seasons for Essex than that of 1979; he took 106 wickets when his county won their third Championship in 1984. But he can have enjoyed few weeks quite as much as June 9-15 in that year of the first title, when he took 26 wickets in six days. Lever’s 13-117 completed his team’s 99-run win over Leicestershire at Chelmsford and he then complemented McEwan’s double-hundred by taking took 13-87 at Edgbaston.

Lever took 53 wickets that June and he finished the season with 99 in the County Championship. Any disappointment felt at not taking one more was probably assuaged by the arrival of the title and the golden trophy.

“Essex were, and still are, a great county to play for,” said Trevor Bailey, a cricketer who remained loyal to his county when it was so skint that members were encouraged to give the county their Green Shield stamps, the income from which helped pay the players. “Although they have played the game seriously and keenly,” he continued, “there has always been an abundance of laughter and humour. This is something to be proud of, because cricket which is not enjoyed is not worth playing.”

It would be pleasant though idealistic to think Bailey’s words are as true in the era when Ben Stokes is auctioned off to the IPL for £1.7m as they were in 1979, when Essex won the title and received prize money of £8,000. But maybe such contrasts and disparities make it all the more important to remember the soggy season when Keith Fletcher and his players were smiling not in adversity, but triumph.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, February 24 2017

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here