When the Lord’s men laid a path for future dominance

Paul Edwards looks at Middlesex’s superb side of the 1970s where a certain Mike Brearley was showing all the signs of his supreme captaincy prowess

Mike Brearley seemed an unlikely revolutionary but he did his bit to bring down a hierarchy. There were no red flags, no barricades stormed and no blood running down the walls of Lord’s, but it happened all the same.

To understand the nature of this most civilised of coups we need to go back to 1965, three years after the abolition of the distinction between amateurs and professionals, but six summers before Brearley was appointed Middlesex captain. There was a new skipper at Lord’s that season, though, and his name was Fred Titmus.

Titmus, who had made his county debut in 1949, was a high-class, off-spinning all-rounder who ended his career with 2,830 wickets and 53 England caps to his considerable credit. But he was also an old pro and his address to the Middlesex players before the start of the 1965 season said as much.

“If you think that now you’ve got a professional in charge you’re going to have a democracy, you’ve got another think coming,” he said. “Some of us have got a lot more experience of cricket, ain’t we, JT?”

‘JT’ was John Murray, who had made his debut in 1952. On Titmus’ other flank was Peter Parfitt, who first played for the county in 1956.

Now it should be stressed at once that Titmus, Murray and Parfitt were fine cricketers, who were merely passing on an ethos of time-served seniority which predated them by several decades and was not confined to professional cricket. It was the way things were done. But it was not the way Brearley was to do it.

“You were supposed to know your place,” he said. “You kept quiet, and you learned the game by watching other people. That was the social behaviour of everyone in the country. If you voiced an idea, they would think, ‘Has he played for ten years? No. Well, what’s he speaking for?’ ”

Brearley played under Titmus in 1965, but then more or less left professional cricket in order to study at Cambridge and California and teach philosophy at Newcastle University. In 1971 he was made Middlesex captain and stated a commitment to play “purposeful cricket”. He was also determined that every voice, however junior, should be heard. The county had not won the Championship since 1949.

There was an immediate improvement under Brearley, but it was tough going. Having finished next to bottom under Parfitt in 1970, Middlesex ended the 1971 season in sixth place but were not to finish higher in any of the next four seasons. In 1975 they reached the finals of both limited-overs competitions but lost to Leicestershire and Lancashire.

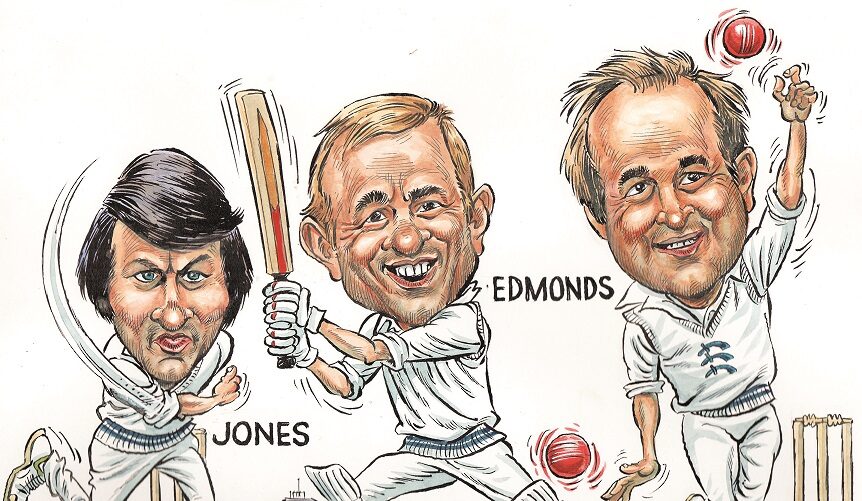

Yet by 1976 Brearley had clearly assembled a side capable of challenging for honours and it included a splendidly diverse mix of personalities. To open the bowling with Mike Selvey, who had been recruited from Surrey, Brearley signed Alan Jones, whose services had already been dispensed with by Sussex and Somerset and who was on the point of emigrating to New Zealand.

“Jones had earned the reputation of being temperamental, hard to handle, lazy in the field and generally more trouble than he was worth,” wrote David Lemmon. But where other counties saw a bloke who was bad news, Brearley saw a fast bowler who needed to be reassured of his worth but never indulged. Jones played in every Championship match for Middlesex in 1976 and finished as leading wicket-taker with 69 victims. He and the admirable Selvey dismissed 130 batsmen that season.

It was a sweltering summer, the hottest on record in England, and one in which spin bowling was to prove vital in deciding the destination of the title. Middlesex were expertly served in that department by the seemingly unlikely combination of the diminutive Titmus, who was by then the only survivor from the old guard of ’65, and the tall, slow left-armer Phil Edmonds, who had taken five wickets on his Test debut against Australia a year previously.

Titmus and Edmonds were strong-minded cricketers and both were known to have their differences with the captain. Yet what emerges strongly from Brearley’s classic book, The Art of Captaincy, is that good leadership is often based on the ability to recognise tensions and harness them productively. Better that, on any account, than a rigid chain of command based on nothing more substantial than time in harness.

Titmus drifted the ball away from the right-handed batsman and turned it in; Edmonds swung it in and turned it away. The pair combined to take 129 wickets in 1976. Norman Featherstone’s well-flighted off-spin accounted for another 32. As the pitched crumbled in August’s unrelenting heat, this trio came into its own. Titmus and Featherstone took 18 wickets in the defeat of Derbyshire at Lord’s and the three spinners dismissed 15 Glamorgan batsmen in the 186-run victory over Glamorgan at Swansea.

All of which, as even the rookie skipper of a club’s Under-11 side will tell you, is only of limited use if you do not have batsmen capable of scoring sufficient runs to test your opponents. Here again, though, Middlesex were richly endowed in 1976.

The leading scorer was Graham Barlow, a 26-year-old Loughborough graduate whose 1,282 runs included centuries in the victories against Sussex, Derbyshire and Essex. But Barlow’s contribution to Middlesex’s success extended well beyond his pugnacious left-handed batting. In company with Nottinghamshire’s Derek Randall, he set new standards for fielding at cover and mid-wicket; his athleticism and the quickness of his pick-up and throw did wonders for the morale of bowlers.

Writing 40 years later, when spectators expect to see fine fielding in all forms of the game, it is as well to be reminded that the 1970s were a decade in which a portly middle-order batsman could still keep his place in a county side and in which some tall fast bowlers patrolled third man or long leg with the aldermanic gravitas of policemen on patrol.

The Middlesex vintage of 1976 may not look athletic on old film when compared with a modern T20 county outfit, and it certainly proved difficult to find a replacement for the wicketkeeper, John Murray, who had retired in 1975, but this was not a team which tolerated slovenly fielding. Barlow’s brilliance set a formidable benchmark, but the ethos of the group was similarly powerful in setting standards. Other Middlesex batsmen enjoyed an excellent season in 1976. Brearley’s opening partner, Mike Smith, scored over 1,000 runs and proved a more-than-capable deputy when his skipper was cast upon the tender mercies of the touring West Indian side for two Tests. Clive Radley played important innings and he and Smith were valuable lieutenants for the captain.

The pattern of that season reflected the keenly competitive nature of county cricket in that era. Sussex led the table in the early weeks of the campaign, but Middlesex’s four wins in 17 June days enabled them to take over. This sequence of victories included a vital triumph at Gloucester which was completed in a trifle more than 11 hours’ playing time and illustrated the many strengths of the future champions.

Brearley was away at the Lord’s Test. Smith inserted the opposition on a damp wicket and Gloucest-ershire were hustled out for 55 by Selvey and Jones in 23.2 overs. Seventies by Edmonds and Barlow helped Middlesex to a 246-run first-innings lead and the spinners claimed all ten wickets when the home side made 131 in their second attempt.

Gloucestershire were one of three sides to win nine games in 1976 and Mike Procter’s side eventually finished third in the table, 24 points behind Middlesex, who enjoyed 11 victories. Between them was only Northamptonshire, with whom the eventual champions had drawn an early season game at Lord’s. Indeed, the title was not secured until four o’clock on the second day of Middlesex’s final game of the season when their three bowling points against Surrey at the Oval and Gloucestershire’s failure to take nine Derbyshire wickets at Bristol brought the outright title back to Lord’s for the first time in 27 years.

“We could be better next season and should remain a very good side for the next five years,” said the skipper. It was a characteristically prescient comment. Middlesex shared the title with Kent in 1977 and won it again in 1980. They took the pennant once more in 1982, Brearley’s last season as a professional cricketer.

By then, of course, the Middlesex skipper had also captained England in home and away Ashes victories and famously been hailed by the Australian fast bowler, Rodney Hogg, as possessing “a degree in people”. Yet Brearley’s reputation as something of a mage was learned in the hard school of English professional cricket. Toughness was not the first quality most people mentioned when explaining his strengths, yet it was as valuable as his intelligence or insight.

As one of his Test colleagues was to comment later: “Mike is a good Test captain because he went through a baptism of fire at Middlesex.”

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, March 17 2017

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here