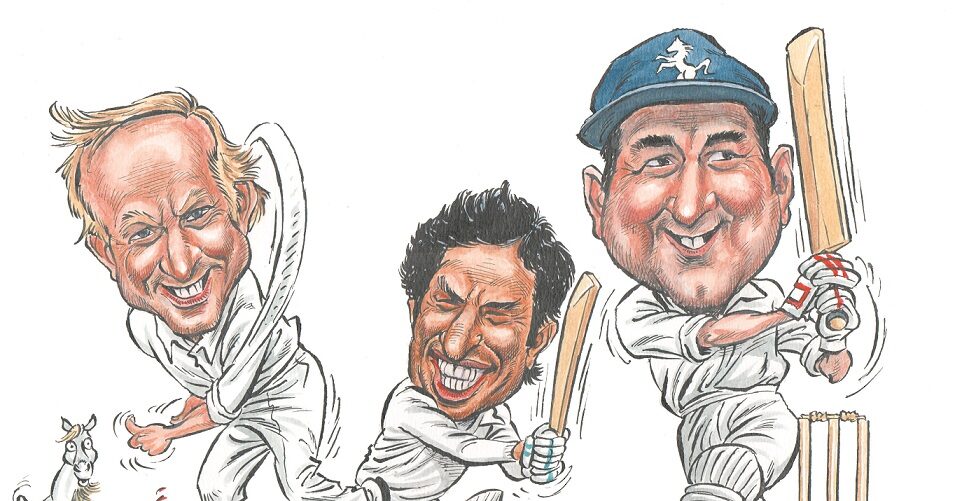

Led by the people’s champion, Colin Cowdrey

At a time when politics were taking over cricket, Colin Cowdrey’s Kent side was displaying the togetherness of true Champions, writes Paul Edwards

Memories are like strands of wool: a word or image from the past can bring a whole skein of recollections tumbling out, overwhelming one with their tangled contrasts and apparent disconnection.

The summer of 1970 has long been the stuff of cricket history, but just a few pages in Wisden take us back to it: here is Tom Graveney leaving Worcester’s outfield for the last time; and there is Jack Bond, lauded as one of the ‘Five Cricketers of the Year’ after a summer in which he had led Lancashire to both a Gillette Cup win and the county’s second successive Sunday League title.

More than most editions, the 1971 Wisden is dominated by politics and events off the field. South Africa had been due to tour England the previous summer, but the sporting world was realising the obscenity of playing games against a country whose government imposed apartheid on its people. While one would like to think it was moral principle that caused the Cricket Council to withdraw their invitation to South Africa, the truth is that government pressure, itself fuelled by fears of massive demonstrations and Commonwealth ostracism, played the major role.

Instead of Ali Bacher’s team, an extravagantly talented Rest of the World side, which always included at least four South Africans, played five unofficial Tests, winning all but one of them. Thus Graeme Pollock could be photographed walking off a ground in the company of his captain, Garry Sobers, something which could never have happened in Pollock’s homeland. It became, in its way, a great season.

And look, here is the Kent team, achievement written on every smile in the picture taken after they had become County Champions for the first time since 1913. They had secured the title with bonus points from their away match against Surrey in September, and there we see 16 contented cricketers, hops strewn on the Oval outfield and empty gasholders in the distance.

Sitting in the middle of the front row is the skipper, Colin Cowdrey, whose 112 on the previous afternoon had settled the destination of the Championship. John Arlott called Cowdrey’s innings, “A century of mature technique and perfect temperament”, and perhaps that praise was informed by the knowledge that the Kent captain had produced some of his best cricket at the end of one of his toughest seasons. That April, Cowdrey had had good reason to hope that he would play five Tests against South Africa and be appointed to captain the MCC team to tour Australia and New Zealand in the following winter. His tenure as England skipper had only been interrupted when he snapped an Achilles tendon the previous May, but he had made a full recovery and was ready to resume his leadership once fitness and form had returned. That, at any rate, was the plan, but it reckoned without a number of factors, one of them being the formidable Ray Illingworth.

The Leicestershire skipper had been appointed England captain in Cowdrey’s stead, and he had done the job well. New Zealand and the West Indies had been defeated in 1969, and Illingworth had demonstrated both his shrewdness and skill as a cricketer. England’s 4-1 defeat to the Rest of the World was not the fault of the captain, who had been his side’s leading run-scorer against one of the best attacks in the game.

Some reckoned that Illingworth’s combination of grit and acumen were what was needed on an Ashes tour. Others felt it was somehow Cowdrey’s right to lead the side: “Justice as well as romance seemed to point to Cowdrey,” explained his biographer, Mark Peel. “He was, after all, the Grand Old Man of English cricket, the survivor of four previous Australian tours, three of them as vice-captain”. Alec Bedser and his selectors, though, chose realism before romance and decided in favour of Illingworth. Cowdrey accepted the invitation to be vice-captain only after pondering the matter for a week or so. “Anyone who had to think more than one second about it should forget it,” said Richie Benaud in the News of the World.

The 1970 season had already tested Cowdrey in other ways. His first 13 Championship innings had yielded only 152 runs and he had asked not to be selected for the summer’s first Test. But inspired by Kent’s visit to Tunbridge Wells – and who would not be? – Cowdrey scored hundreds against Sussex and Essex and returned to a national team which already included his county colleagues Brian Luckhurst, Alan Knott and Derek Underwood.

All of which only made greater demands on the second XI players drafted into a Kent side which was bottom of the Championship table on July 1, having won one of their nine matches; it seemed the county’s Centenary would be celebrated with stale beer. An unbeaten century by the stand-in skipper, Mike Denness, and some fine bowling by the seamers secured an innings victory over Essex at Harlow, but that was followed by a 136-run loss to Middlesex at Lord’s.

After the first day of the match against Derbyshire at Maidstone, the patience of Kent’s Secretary-Manager, Les Ames, finally snapped. A formidable wicketkeeper-batsman who played 47 Tests, Ames had been one of the best strokemakers in the land and he could not abide cricket that was either turgid or incompetent.

As he watched Derbyshire crawl to 238 for eight, he decided to administer what today would be called a ‘bollocking’. Come to think of it, Ames might have called it that as well although the incurably diplomatic Cowdrey may have suggested that the old warhorse had “reminded the players of their responsibilities”. Either way, nobody escaped censure and nobody failed to respond. Kent won seven and lost none of their remaining 13 games.

The resurgence of Cowdrey’s team was helped by the fact that while there were several good county sides in 1970, none played outstanding cricket throughout the season. Seven teams led the table at one time or another, and it was relatively easy for Kent to make up ground once they had rediscovered their best form.

The presence of the Rest of the World side in England did not harm their chances either. For while some counties lost players to the tourists, neither the Pakistani batsman, Asif Iqbal, nor the Barbadian bowler, John Shepherd, was called up. Both players saw Kent’s white horse badge as much more than a flag of mercenary convenience. Asif’s 1,379 Championship runs were second only to the admirable Denness’ 1,445 in the final averages, while Shepherd’s 84 wickets and 695 runs may have been even more valuable. Kent’s two overseas cricketers and the off-spinning all-rounder, Graham Johnson, were the county’s only ever-presents during a season in which 14 players made 11 or more appearances.

Much as the notion may be disparaged, there was a momentum to Kent’s cricket in the high summer of 1970. Underwood, that prince of slow-medium left-arm spinners, took five for 40 and shared nine wickets with Johnson as Somerset were beaten by ten wickets at Weston-super-Mare. A week later, at Cheltenham, Denness’ team saved the follow-on by one run and then chased down 340 to win by one wicket.

Asif made a century in that victory against Gloucestershire, and then another against Surrey at Blackheath. Not content with that, the Pakistani all-rounder completed a brilliant running catch off the penultimate possible ball of the latter game to seal a 12-run victory. “We shall win it at the Oval,” Asif had told Cowdrey in early August. “There’s nothing to worry about. We shall all be drinking champagne at the Oval.”

Perhaps a few of his early-season cares fell away from Cowdrey, too. Despite his wretched start and then missing nearly a third of his county’s games due to Test calls, Kent’s skipper still made 1,013 Championship runs in 1970 and finished top of the averages. The redoubtable Luckhurst, his virtues so often unsung until he made two centuries in that winter’s Ashes, missed one game more than Cowdrey but scored only 11 runs fewer. Two wins at Folkestone – Kent used eight grounds that summer – meant that only bonus points were needed at the Oval.

And so we return to that team photograph and a smiling Cowdrey sitting amid his victorious players. At first glance he seems the antithesis of his rival, Illingworth. Urbane and suave, he appears an Establishment bloom when compared with the ‘muck or nettles’ Yorkshireman. And almost certainly, he was not as astute a captain.

Yet Cowdrey faced Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller in his first Test match and Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson in his final series. He had also faced Wes Hall and Charlie Griffiths at their bowl-loosening best. He did not want for courage in any of its forms, and not for an instant did he lack love for the county he led to a famous title in the beguiling summer of 1970. Those feelings were more than requited for a cricketer who regarded the St Lawrence ground as an earthly paradise and playing for Kent as one of the greatest honours that could come a chap’s way.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, January 27 2017

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here