Derek Pringle: How players have bent but not broken the rules in cricket

If there is many a slip twixt cup and lip, the same can be said for the moral limbo land that seems to exist between cricket’s laws and rules and that woolly concept – “the spirit of the game”.

It was in that spiky no-man’s land that Carew Cricket Club found themselves recently, chastened by none other than that well-known paragon of virtuousness, Piers Morgan. In a series of tweets, Morgan, a keen village cricketer in his day, unloaded his scorn, calling Carew a “spineless, cowardly bunch of pathetic numpties”, whose actions had been “shameful”. Their crime – to win their local league by one point after deliberately gifting closest rivals, Cresselly, a win without the chance of bonus points after declaring their own innings on 18 for one after just 2.3 overs.

One query, from afar: why wait until they reached 18 for one? Was the idea one that suddenly came to them? After all, 18 runs from 15 balls strikes me not as pre-meditation, but as putting bat to ball with intent.

Their actions, though unsporting, were within the rules of the competition – Division One of the Pembrokeshire County Championship. As such, they were duly crowned champions though as in all these matters when there is a big enough outcry, those who make the often asinine rules bow to public opinion, have a meeting, then find in favour of the wronged party.

This has always struck me as a contradiction. Players and teams are asked to abide by Laws and various regulations, but are punished if they find a loophole in them. Even players who deliberately break the Laws by cheating are treated with less opprobrium than those who have the cunning to find a way round them. But then it is more in the British character to applaud the up-front rogue than the smarty pants chancer.

That was certainly the case for Brian Rose and Somerset, who, in 1979, declared on 1-0 in their Benson & Hedges zonal match against Worcestershire, an act that guaranteed them passage to the knockout stage. Two teams, Worcestershire and Glamorgan, could equal Somerset on points but could not match their strike-rate (the decider for teams level on points before net run-rate was used) unless they were beaten heavily by Worcestershire.

Some clever clogs in the Somerset team (no names) worked out that if they declared after an over, their strike-rate would not be affected and while Worcs would win, Somerset would still be top of the table, a position that also won you a home tie. The game was over in 18 minutes, including the 10-minute break between innings.

Unsurprisingly, there was uproar in the media and from the public, though to be fair to Somerset, a team containing Ian Botham, Viv Richards and Joel Garner, they had checked with various authorities to see if it was legal. It was, but that did not stop the Test & County Cricket Board barring Somerset from further participation in the tournament, eventually won by Essex as they notched the first trophy in their history.

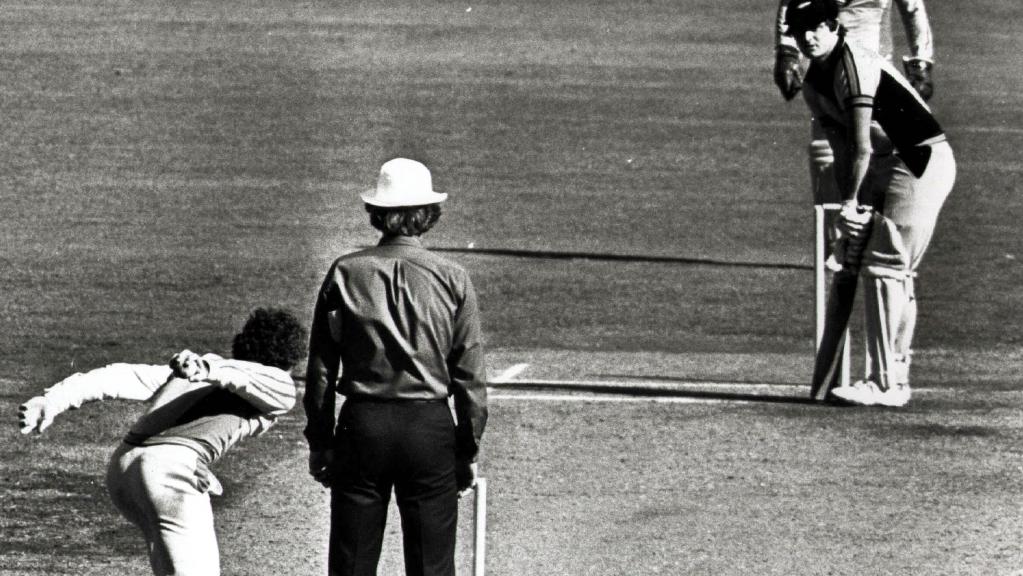

Such acts may not be sport, but they are acts of self-preservation – something all professional sportsmen will, if pushed, admit to as a large part of their motivation. Carew are amateurs playing for beer and glory alone, but Trevor Chapple wasn’t. On instruction from brother Greg, he rolled the final ball of a one-day international against New Zealand at the MCG along the ground – a legal delivery back then but most definitely underhand. The Kiwis, arch- rivals, needed seven runs to win with one ball remaining, but Greg Chapple did not want to give them a chance even to tie the match, which is why he told his younger brother to underarm it to Brian McKechnie, an All Black rugby player with a decent hit on him. The furore was immense and even now New Zealand teams use the injustice as motivation whenever they play the Aussies.

Unsurprisingly, the Laws were immediately amended to close the loophole and prevent such cynicism from recurring (a no-ball is now called if the ball bounces twice before it reaches the batsman).

Winning at all costs, especially in cricket, was frowned upon until the Packer years. Thereafter, the win bonus and prize money became an obvious way to boost wages that were never that great despite the shake-up caused by the World Series. As a result, players began to place self-interest above their wider responsibilities of entertaining the paying public, with the more studious studying the fine print in the many Laws and regulations.

Even England captains were not above accusations of bringing the game into disrepute.

In 1979, Mike Brearley was fully within his rights to place every fielder, including wicket-keeper David Bairstow, on the boundary in a one-day match with West Indies needing four runs off the final ball. The crowd didn’t like it and he was vilified in the press when England prevailed, though that tended to be the lot of Pommie captains in Australia for matters far less inflammatory.

The regulations were changed following that incident too, setting a pattern for these things that has prevailed right up to the recent law changes around running out batsmen backing up too far.

That is fine but the authorities and lawmakers tend to punish those who find weaknesses in the clauses and not those who make them, and that cannot be wholly just.