(Photo: Getty Images)

By Martin Johnson

When Arsene Wenger opted to serve a touchline ban in the press box recently, I found myself hoping Trevor Bayliss might consider following the Arsenal football manager’s lead – if only to spare us those close-up shots of him on the balcony.

If you’re wondering what they remind you of, next time you’re behind a car with one of those nodding dogs in the back window, try and picture it with a floppy sun hat on.

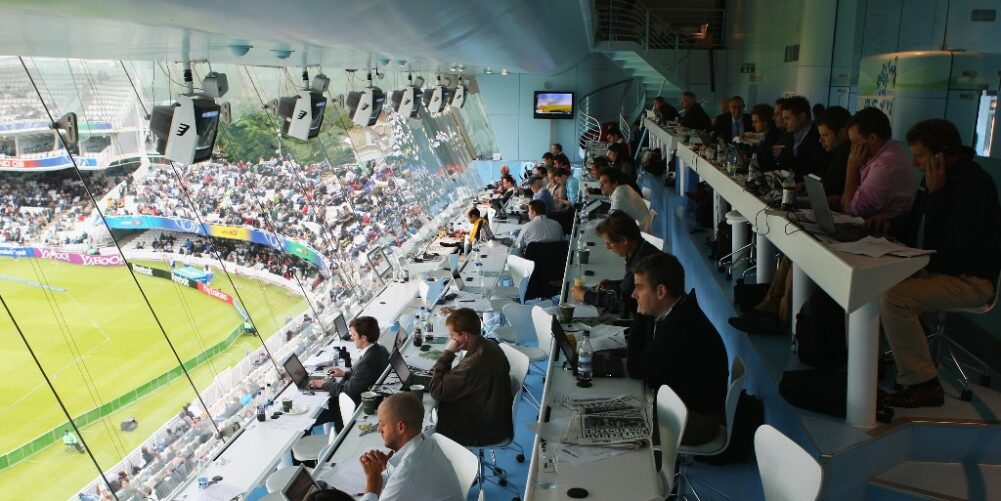

This winter’s Ashes series won’t have been much fun for an English cricket hack in Australia, largely because there is nothing quite so nauseating as a press box full of Aussie journos when their team is sticking it to the Poms.

With the England coach in the box, though, they could have at least lightened the mood with a few questions. “So, Trev. Now that you’ve kindly agreed to stay in charge for another two years, tell me. What exactly is it that you do?”

Unlike soccer, or rugby, they can be long old days in a cricket press box, and when it’s a dull old game, or rain stops play, Bayliss himself might find it an agreeable change helping compile an all-time Ugly XI, or offer helpful suggestions to a journalist struggling to come up with a catchy intro.

Which is why, when Darren Gough made his debut for Yorkshire at the age of 18, he was fairly startled to pick up the paper next morning and find himself described as the son of a Barnsley rat catcher.

Given that Gough senior was an office bound pest control officer for Rentokil, this was one of the better examples of creative writing.

For reasons that entirely escape me, journalists are never more closely associated with creative writing than when they’re filling in an expenses form, and one of the all-time legends in this area cemented his place in the hall of fame on one rainy 1980s afternoon in the Yorkshire press box.

When there’s nothing to do but wait for the next inspection, conversations can fly off in almost any direction, and on this occasion it happened to be motor cars. With someone wondering out loud why, when the car’s going backwards, the mileometer doesn’t budge.

“Bloody hell!” came the cry from our man. “My driveway’s about 70 yards long, and I back out it every day.” Which resulted in him billing his employer for 30 years’ unclaimed “reverse mileage”, and even more remarkably, they coughed up.

Sadly, the decline of newspaper cricket coverage for domestic matches means press boxes are nothing like as well occupied as they once were, and no longer – in places like Yorkshire – the dangerous places they once were for the shy and nervous newcomer.

The gnarled old hacks in the Yorkshire box would quickly start their favourite game of “dupe the new boy”, which began after the first wicket of an innings. “It’s nine isn’t it?” someone would say. “And all the other old stagers would pipe up: “Yes, it’s nine.” The hidden meaning being that the wicket taker now only needed another nine wickets to end up with all ten. Ho, ho, ho.

And when the same bowler took the second wicket it would be: “That makes it eight doesn’t it?” “By heck, you’re right Jim. It’s eight.”

And all the while the poor old new boy at the back would be wondering what an earth they were all on about, and worried stiff that he might be missing some huge story.

As japes go, it could scarcely have been more juvenile, but it was just one of many ways of getting through a boring day.

In the 1980s you needed to get to the ground early to bag a seat in the press box, and earlier still if you wanted to bag the plum positions. The most dangerous seat in the Worcester box was in the second of three rows, right behind Jack Bannister of the Birmingham Post. Not that Jack wasn’t a delightful man, but when Jack told a story, especially about cricket, it could take up an entire session.

It took me a while, but when I got a bit more experienced, I was ready for it. Graeme Hick would hit a four to bring up some landmark, and Jack’s chair would start to revolve. At which point I would tactically drop my biro, leaving the bloke directly behind in Jack’s line of fire, and I’d spend the next half hour on the floor listening to Jack battering his victim with an avalanche of “interesting” statistics. In those days, the top writers did not, as is the case today, confine themselves exclusively to international cricket, and John Arlott would be a regular visitor to the humblest of press boxes.

And if it was your first experience of him, you couldn’t help but be impressed when he arrived with two enormous briefcases. Until he opened the first one to retrieve his bottles of wine, and then the second one to pull out his rack of glasses.

On one occasion, in the old windowless wooden shack which passed for the press box at Dean Court in Bournemouth, Arlott disappeared in mid morning for lunch at a local wine bar, and didn’t re-appear – looking slightly ruddy of cheek – until about 5pm. He pulled out a typewriter, bashed out a paragraph, pulled it out to examine it, and uttered two hearty expletives when a gust of coastal wind plucked it from his grasp and over extra cover.

He sighed, put his head down, had a nap, and somehow woke up to compose a highly readable piece for the next morning’s Guardian.

Dictated over the phone, not by Arlott, but by one the locals to whom he had given a fiver. None of your fancy wifi and Bluetooth contraptions in those days, otherwise my favourite copytaker story of all time would never have happened.

Copytakers in those days wouldn’t have uttered anything more effusive than a weary grunt if they’d had Shakespeare on the phone, or Lord Byron, never mind some old hack from the Daily Express. Charged with supplying 500 words, and wanting to check on his progress, our man stopped to ask: “Could you tell me how many words I’ve done so far?” To which the reply came back, in deadly monotone: “Enough.”