Johnson column: Sandpapergate was so hysterical it’s a wonder the EU hasn’t expelled Australian diplomats

(Photo: Getty Images)

By Martin Johnson

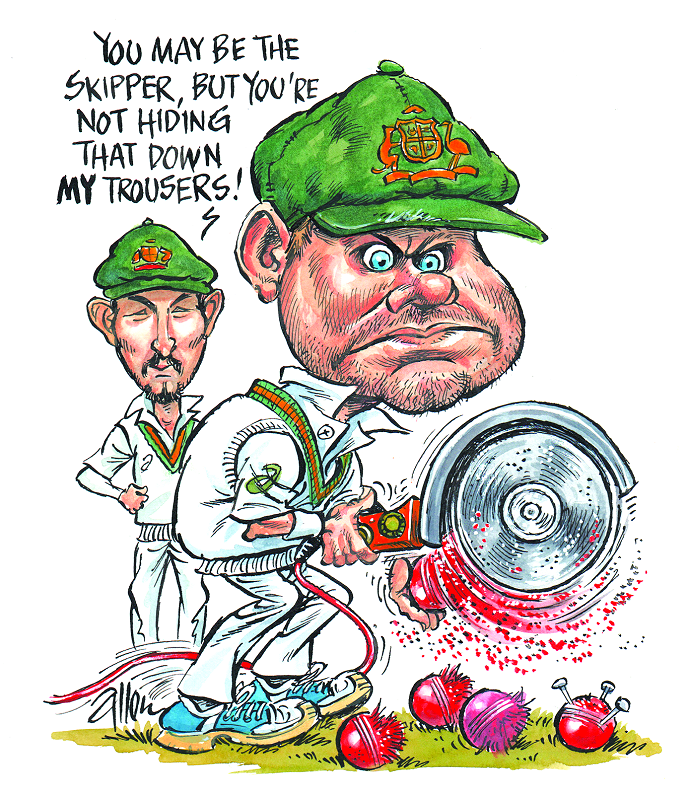

Every cloud, as they say, and with Test cricket struggling to pay the bills nowadays, I think I spy a commercial opportunity. How about “B&Q – official ball tampering suppliers to the Australian cricket team. Put an end to all that tiresome rubbing and scraping. Our new electric sander range does all the hard work for you!”

Or maybe one of those outdoor camping outlets with the multi-pocketed trousers. “With our Kilamanjaro range, the match referee will never find where you’ve hidden that Swiss Army knife.”

You’ve got to hand it to Steve Smith and the boys. It takes a special talent to turn an offence that ranks no higher than No.2 out of the four ICC conduct codes into such an international cause celebre that Brexit talks may have to be put on hold while the EU debates on whether to start expelling Australian diplomats.

What I’d like to know is how an Australian cricketer qualifies for admittance to the team’s so-called “leadership group”. Is there an entrance exam perhaps? If so, it can’t be very taxing. “Q1. What’s a Jolly Swagman?

- A) A pub? B) A happy bank robber?

- C) Someone who sits under coolabah trees waiting for his Billy to boil?”

Which would certainly explain why, during that fateful lunch break decision to issue the team’s most junior member with a Heath Robinson contraption that couldn’t possibly be operated without getting himself noticed, no-one thought to pipe up: “Just a thought skipper?

But anyone know if this game’s being televised?”

TV coverage is now so intrusive that the cameras hone in on everything. Someone in the crowd during the Cape Town Test will have gone into work the day after claiming a sickie to face a tricky interrogation. “Ah, Brown. Do you have a twin brother? The bloke swigging lager up by the Castle Lager Braai yesterday looked uncannily like you.”

And those days when a player could happily pick his nose on the balcony in the belief that it was an entirely private affair have long gone.

The thing about ball tampering incidents is that most of them have elements of comedy. Such as Shahid Afridi, in a 2011 ODI in Perth, apparently mistaking the ball for a Cox’s orange pippin and taking a large bite out of it. I don’t know where the ball is now – perhaps behind glass in some museum of shame – but when the first big tampering case in England took place in 1992, the ball mysteriously disappeared.

It all began at Lord’s during the fourth of five ODIs, when the match umpires ordered the ball being employed by Pakistan to be changed during the lunch break on suspicion that it had been tampered with. Plunging the ICC into their default status of panic.

The ICC president Colin Cowdrey quickly made himself scarce by hopping onto a flight to India, leaving the chairman, Col John Stephenson, to spend the next six days riding around St John’s Wood on his bicycle issuing statements. Only one of which failed to contain the words ‘no’ and ‘comment’.

This was the last one, claiming that the ball would not be coughed up for inspection on the grounds that it might be “prejudicial” to any legal action. In fact, he had no idea where the ball was, as it had been pocketed by third umpire Don Oslear, ending up as a trophy on the mantelpiece of his Cleethorpes bungalow.

An even bigger row followed in 1994 over the so called “dirt in the pocket” affair, again at Lord’s, on the third day of the first Test between England and South Africa. Not untypically for matches broadcast on the BBC at the time, the hosts were showing some horse racing when South African viewers were being treated to live pictures of Michael Atherton applying dirt to the ball.

During the tea interval, with the Beeb having now returned from the 3.45 at Wincanton, or whatever it was, rumours reached the England dressing room of a possible ball investigation. When, and against whom, no-one could be sure, prompting Graham Gooch to pipe up: “Well it can’t be us. Their batsmen are smashing it all over the park.”

Eventually the footage reached the home audience. “Interesting,” said Richie Benaud, which was Richie-speak for “cor blimey, wot’s going on ’ere then?” And by close of play, the England captain was in the headmaster’s study/ICC match referee’s office, explaining events to Peter Burge. And leaving it with nothing more than a mild ticking off.

And there it might have ended had it not been for Burge bumping into the England manager Ray Illingworth later that evening back at the team hotel. “How did Michael explain the dirt?” inquired Raymond. “Dirt? What dirt?” replied Burge. “He never mentioned any dirt”. “Ah….” said Raymond. And the rest we know about.

What’s changed the nature of ball tampering is reverse swing. It used to be done to lift the seam, with someone like Ken Higgs so proficient at it that he could turn his right thumb into the equivalent of an electric can opener with a single one-handed twirl. Roughing up an entire side of a ball is not so easy to camouflage, so how did the Australians put themselves into a position in which it was almost impossible not to get rumbled?

The answer may be the country itself. Long gone is the place of romantic legend, where men were men, sheilas were sheilas, and any salt water crocodile daft enough to approach a billabong camp fire ran the risk of being punched on the nose and skinned alive by men with skin like a dried up river bed inflamed on several gallons of Fosters.

Nowadays, though, there is no more namby pamby place on planet earth, with danger of death warnings posted for everything, from not putting on your sun hat, to using the tip-up seats at the SCG. Cross the road before the little green man tells you to? You’re nicked mate.

You can get deep-vein thrombosis waiting to cross the extra wide roads they have in Adelaide, so Jonathan Agnew decided that (at gone midnight, on a deserted side street during the Ashes) he’d rather not wait. Bingo! Flashing blue light, and collar felt.

So now you know. With the end of the tour in sight for Steve Smith’s men, facing an imminent return to having your life ebbing away waiting for little red men to turn into green ones, the urge to do something naughty was nigh on irresistible.