Johnson column: Ok, you’ve beaten death but can you bat No.3?

The on-field verbals in St Lucia have turned out to be a bit more spicy than the anodyne stuff you normally get out in the middle (“I’ll bowl you a piano, see if you can play that…..”) and it may be time to enhance the TV viewing experience by relocating some of those stump microphones to the dressing rooms. Especially England’s, where stitching together all the conversations about who should be batting at No.3 would be cricket’s equivalent of the Watergate tapes.

“How about you Joe?” “Sorry, captain’s prerogative.” “Bluey?” “Down the order for me. With the gloves if you don’t mind.” “Moeen?” “Been there, done that, and not very well as it happens.” “Jos?” “ Sorry coach. Give me some time to think about it. A couple of years should do.” “Okay, Stokesy then. Stokesy? Stokesy?” “I think he’s just gone to the lavatory, Trev. Could be gone for some time.”

In an ideal world, Joe Root would put his hand up, but you can understand his reasoning. At least at No.4 he manages to get both of his pads on before someone shouts: “You’re in skip!” rather than the customary one, and it also gives him just enough time to have a consoling word with the first man out. “Bloody hell, Keaton. You back again already?”

England’s latest No.3, Joe Denly, was doing the job in St Lucia because the selectors decided that they wanted one more look at Keaton Jennings at the top of the order. This was a bit like – and we’ve all done it – losing your car keys and looking for them, several times over, in the same pocket.

You know there’s nothing in there but a packet of polo mints and a bit of loose change, but maybe, just maybe, your mind’s been playing tricks on you, and on the 15th search they’ll miraculously be there.

Jennings’ second-innings dismissal was unlucky to say the least, so why the broad smile when he looked down to see a bail lying on the ground? Possibly because he knew that this was the last time he’d have to go through all this, and that Bob Willis would now have to find someone else to rottweiler back in the studio.

When they’d finally managed to calm Bob down with a tranquilising dart, the discussion turned to whether, with Denly’s 69, England had stumbled on the long-term solution to the No.3 conundrum. And the verdict? Maybe.

Or then again, maybe not.

The way I see it, though, Denly is an absolute shoo-in. For one thing, the No.3 spot has become the equivalent of a live hand grenade at a pass-the-parcel party, added to which is a fixture list which sees domestic red-ball cricket getting underway at a time of year when the nation’s central heating boilers are still going full blast.

Ergo, any uncapped No.3 trying to make an early case by spending long periods out in the middle will be ruled out for the rest of the summer with frostbite.

Patience is also a key attribute for a top-order Test match batsman, and Denly ought to have plenty of that merely by having to wait until he was nearly 33 before getting his first cap. His first appearance for Kent was 15 years ago (first ball 0 v Oxford University) and he’s old enough to have qualified for a testimonial this year.

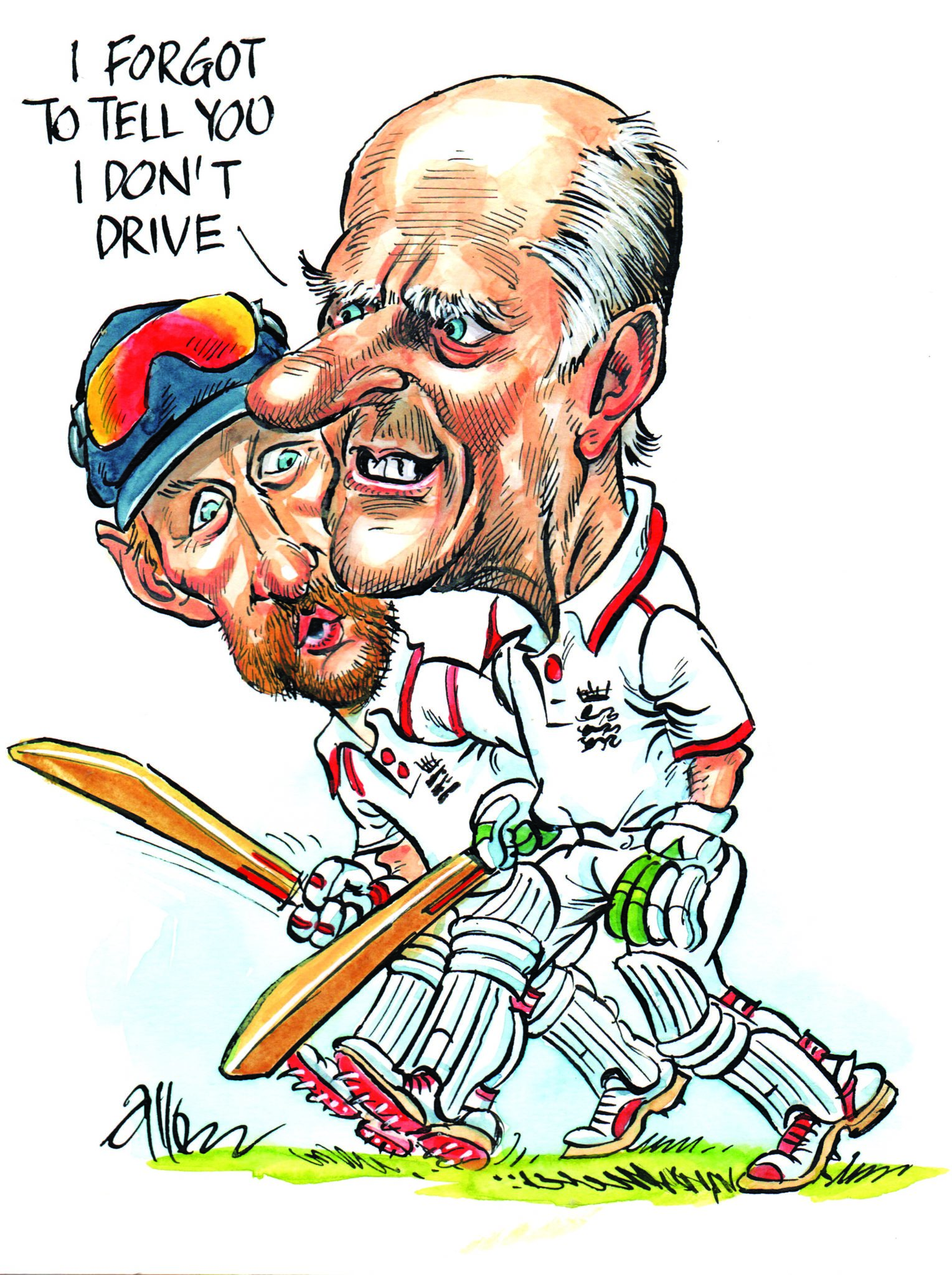

However, cricket is the kind of sport you can play at a high level at a relatively advanced age. You can’t really see Prince Philip driving in Grand Prix for example, but you could just about hide him in the field at square leg, and anyway, of all those cricketers who’ve made Test match debuts when getting on a bit, Denly is practically a youngster.

The oldest debutant for England was a chap by the name of James Southerton, who was well past his 49th birthday when he played in the first-ever Test match between England and Australia in 1877. Although he wasn’t among the four players who were past 50 when they played Test cricket, the oldest of which was another Englishman, Wilfred Rhodes.

Rhodes played his last game against the West Indies at the Oval in 1930 at the age of 52, coming on as first change with his slow left-armers. Slow enough at that age to be almost impossible to hit by the looks of his combined figures of 44.5-25-39-2.

Every weekend this summer, if you wander into a club game anywhere in England, chances are you will see at least one player out in the middle who’s been playing before anyone had heard of the Beatles.

Years ago, I remember looking in on a club match near Stratford on Avon, and watching the new ball being taken by someone who was about 75, and had a one pace run-up. Or stagger-up, to be more accurate. No-one could give a definitive answer to the obvious question: “Why?” But the general consensus appeared to be along the lines of: “Well, he’s always done it. Besides which, his missus does the teas.”

It is even possible to play cricket after you’re dead. Years ago, we had a team of cricket hacks entitled the ‘Fleet Street Wanderers’, and when the captain sadly died of cancer, that summer’s tour of Devon, we decided, would still go on with him in full command.

We purloined, from outside Boots the chemist, a giant cardboard cut out of Alan Shearer advertising a Lucozade sports drink, and when a sports photographer managed to blow up the skipper’s head and transpose it over Shearer’s, our leader spent the entire tour (in much the same way as the Spaniards strapping El Cid to his horse to frighten the Moors) inspiring his team-mates from first slip.

So, if they really can’t find a No.3 for the Ashes, a cardboard cut-out of Peter May should do nicely.

MARTIN JOHNSON | GETTY IMAGES