Tim Wigmore says the competitive balance between the counties is eroding…

It did not take long for Gloucestershire’s warm afterglow at winning the Royal London One-Day Cup to recede. A few days later, James Fuller, one of their leading fast bowlers, rejected a new contract to stay at the county and opted to switch to Middlesex.

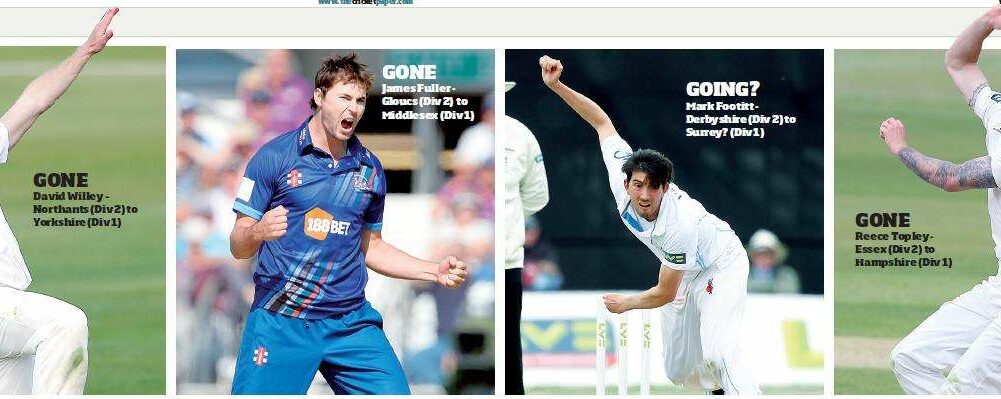

Fuller is not the only player who will be moving from Division Two to Division One cricket in 2016. Reece Topley has gone from Essex to Hampshire, and David Willey from Northamptonshire to Yorkshire. It is expected that Derbyshire’s Mark Footitt, whose haul of 160 first-class wickets in the last two seasons make him one of the premier bowers in county cricket today, will soon follow, perhaps to Surrey.

These player movements are not the only sign of the increasing gulf between county cricket’s haves – those who host Test cricket – and its have-nots. Never has Division One been as dominated by those with Test grounds as it will be in 2016. Of the nine counties who host Tests, only Glamorgan will be absent from Division One. Somerset will be the sole standard-bearers for the other nine counties, and even they will host ODIs in the 2019 World Cup.

The competitive balance in county cricket has not quite reached the levels of La Liga, where Barcelona and Real Madrid claim as much TV revenue as the other 18 clubs combined and are accordingly able to dominate the league completely. Still, the gulf between Division One and Division Two of the County Championship has become akin to that between the Premier League and the Championship in football. Each year the two relegated sides are the favourites to gain promotion, while those who have just been promoted are the favourites to get relegated. It was a minor surprise when Hampshire stayed up at Sussex’s expense in 2015, but even this was crude economics asserting itself: Hampshire benefit both from hosting Tests at the Rose Bowl and having Rod Bransgrove as chairman, two advantages Sussex lack.

Perhaps it is in Division Two where the gulf between counties is most palpable. Division Two has increasingly come to resemble not so much one league as two: those, like Surrey and Lancashire, who regard themselves as having to endure an inconvenient stop there before their inevitable return to Division One; and those who have come to accept it as a permanent way of life.

The upshot has been a dramatic decline in the competitiveness of Division Two. In 2000, the first season of two divisions, just 54 points separated the top and bottom of Division Two. By 2015, the gap was 146 points. Never have two teams in Division Two been as dominant as in 2015: Lancashire, in second, led third-placed Essex by 54 points, the entire gap between top and bottom 15 years ago.

A widening gulf between the best and worst counties is the inevitable result of two divisions, especially since the number of teams promoted and relegated between the divisions was reduced from three to two in 2006, making the County Championship less volatile. Giving teams more to play for, as promotion and relegation does, can modestly lift up the standard of all counties by increasing competitiveness and context in the County Championship. Yet ultimately for Division One to get stronger, Division Two needs to get weaker.

The development is easy to lament, perhaps too easy. For while sporting romance has suffered, the underlying rationale – that Division One strengthens and comes to mirror the intensity of Test cricket – is irrefutable. The 15 years of two-division County Championship cricket have been far more successful for the England Test team than the preceding 15 years.

The curiosity is that the gap has not been apparent in shorter formats of the game. All four finalists in white ball domestic competitions in 2015 came from Division Two, albeit that two were Lancashire and Surrey. Only three of the quarter-finalists in the t20 Blast will be in Division One of the County Championship next season. Remarkably Yorkshire and Middlesex, the top two teams in the County Championship, finished second-bottom and bottom in the two t20 Divisions.

Partly this reflects how Division One counties tend to prioritise Championship cricket. Ryan Sidebottom did not bowl a single ball in white-ball cricket all season, while Jack Brooks played only five games across t20 and one-day cricket. The success of Division Two counties in white-ball cricket also vindicated their pragmatism. It was long clear that neither Gloucestershire nor Northamptonshire would gain promotion so it made sense for them to focus their energies upon white-ball cricket. The financial muscle of counties might also count for less in t20: the sheer length of the Blast means that it is almost impossible to get specialist overseas players for its duration.

Yet, despite the success of lower tier counties this season, Division One sides are likely to become more dominant in white-ball cricket too. Moving t20 cricket to a block will help wealthier counties give more attention to the format. It will also make it easier to get overseas stars. While there was no shortage of overseas talent in the Blast this year, playing in a block – thereby reducing downtime between matches and making it more likely that imports will be available for crux matches – will militate against the less glamorous counties.

In 2000, just after the first season of two division County Championship cricket, Mark Ramprakash moved from Middlesex to Surrey, fuelled by a belief that he needed to be playing in Division One to maximise his chances of playing Test cricket. While players like Footitt, Topley and Willey appear to think the same, the gap between the two divisions will get ever wider unless the ECB act.

The signs are that the ECB are happy for the gap to continue to grow. “The ECB is committed to ensuring counties are in a position to sustain their own business,” chief executive Tom Harrison says. “We are in the business of doing everything we can to put a structure in place for our county clubs to be as sustainable as possible.”

Many will see a certain irony in Harrison’s words: after all, the counties with Test grounds have accumulated the biggest debts.

Yet the language of self-sufficiency bodes ill for those who lack the grounds, catchment area or support base of the largest counties. Inevitably, and through no fault of their own, these counties are unable to match the wages of the Division One elite. It would take an equitable revenue system akin to that used in American Football for that to change, yet county cricket is moving ever further away from the NFL model of sharing wealth.

So Gloucestershire would be wise to cherish the memory of their Lord’s victory last month. Their next triumph might be a long time coming.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper on Friday October 9, 2015