Why Leicester fairytale can’t be repeated by cricket cousins

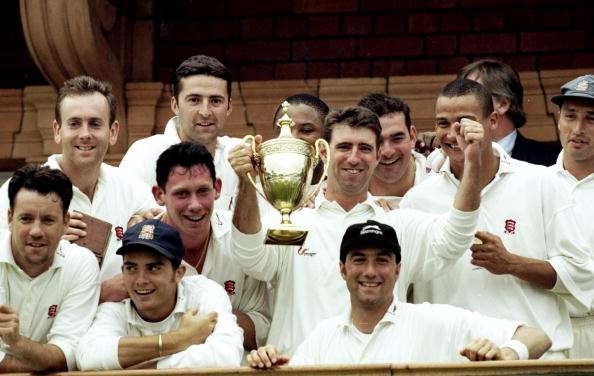

12 Jul 1998: The Essex team display the trophy after the Benson and Hedges Cup final against Leicestershire at Lord's in London. Essex won the match by 192 runs. Mandatory Credit: Lawrence Griffiths/Allsport

Tim Wigmore reveals how county cricket’s finances mean the underdog has had his day in the Championship

Fans of the County Championship have normally had one riposte to being mocked by Premier League supporters. For all the Premier League’s quality and razzmatazz, so the argument goes, county cricket has one thing in its favour: its romance and penchant for tales of underdog success.

No longer. While Leicester City are on the brink of completing their 5,000-1 triumph in the Premier League, county cricket’s Leicester City equivalents seem further away than ever.

In 2016, for the first time, eight of the nine counties in Division One of the County Championship are from Test-playing grounds; the only exception is Somerset, who are widely tipped for relegation. Glamorgan are the only county to have hosted a Test in Division Two and, such is their level of debt and paucity of international fixtures, they can be considered a Test ground in name only.

The introduction of two divisions in 2000 has been a boon for English cricket. It has led to a concentration of talent in Division One, bridging the gap between the county game and international cricket, and the effects can be seen in England’s consistently excellent performances since.

Two decades ago, Leicestershire won two Championship crowns in three years with a motley assortment of local talent, cast-offs from other counties and, in Phil Simmons, a sprinkling of Caribbean flair.

A repeat of this story might be more likely than Leicester City winning the league seemed at the start of the season, but not by much. Getting out of Division Two and avoiding immediate relegation are onerous enough for clubs of Leicestershire’s size. Not since 2007 have any of Derbyshire, Gloucestershire, Glamorgan, Leicestershire, Kent and Northamptonshire spent a season in Division One without getting relegated.

Along the way the gap within Division Two, between clubs just passing by for a season or two and those marooned there, has morphed into a chasm. In 2000, the first season of two divisions, just 54 points separated the top and bottom of Division Two. By 2015, the gap was 146 points.

What has happened reflects how the decks have become stacked against county cricket’s Leicester Citys. There is no better example than Leicestershire, bottom of Division Two in the last three seasons and four of the last five.

It is no indictment of a lack of talent produced by Leicestershire since their Championship triumphs in 1996 and 1998. Stuart Broad, Harry Gurney, James Taylor and Luke Wright have all emerged through Leicestershire’s system; so, too, have Josh Cobb, Greg Smith and Shiv Thakor. Together this amounts to a coterie of players easily good enough to be an established Division One county and even, perhaps, to challenge for the title.

But all seven have long since left Leicestershire, including four to Nottinghamshire alone. It is a microcosm of how, in the era of two divisions, players with international ambitions are driven to move away from Division Two to further their England aspirations.

It is indicative, too, of how the financial gulf between counties has increased, and that players can earn far more by moving away from a less fashionable county. In 2014, the most recent year for which accounts are available, Northants had a turnover that was less than one-sixth of Surrey’s.

Domestic T20 has driven the increased financial disparity, allowing counties who play on larger grounds – normally Test venues – to pack in bigger crowds and generate more funds to invest in their squads for the three formats of the game. And, following the introduction of London weighting from 2016, the salary cap for Middlesex and Surrey has been increased, giving them even more cash to entice talent from other counties.

Since the end of 2015 alone, Mark Footitt, Reece Topley and David Willey have all moved from Division Two to Division One. All can legitimately claim their moves are driven by their international ambitions, but they all enjoyed significant pay hikes that certainly made moving counties more palatable.

It is not only England players who are moving from Division Two to One. Overseas players, too, are abandoning the less fashionable counties. Courtney Walsh played for Gloucestershire over 15 seasons but, now, surely, would be enticed by a more lucrative offer to Division One.

After stints at the unfashionable trio of Derbyshire, Northamptonshire and Leicestershire, Chris Rogers was lured to Middlesex, and now Somerset; Kane Williamson, spotted by Gloucestershire before he was a star, now plays for Yorkshire.

Division Two counties know as much. As promotion to Division One has come to seem an ever-more fantastical dream – and it will be even more so from 2017, when there are only eight berths in Division One – so Division Two counties have come to focus on white-ball cricket, knowing it represents their best chance of success.

In limited-overs cricket some romance lives on. In 2011 Leicestershire won the T20 Cup despite finishing 61 points adrift at the bottom of Division Two. Gloucestershire and Northants, mid-table Division Two sides, both reached a white ball final last year, with Gloucestershire triumphant in the Royal London One-Day Cup; Northants won the T20 Blast in 2013, too.

All the while the attention of poorer counties has slipped ever further away from the County Championship. ECB player payments incentivise counties to pick players under 26 (under 28 in the case of spinners). When Division Two counties realise promotion will be beyond them for another season, there is a rationale in them packing their first-class team with younger players to give them more funds to focus on other competitions.

Angus Porter, former Professional Cricketers’ Association chief executive, said recently: “Some counties, rather than try to compete to win, have used the Championship in a different way: to maximise the performance-related ECB payments received for selecting young players, as a way of getting additional income to compete in white-ball cricket.”.

The tale of Leicester City has gladdened the hearts of sports fans the world over.

In T20 and one-day cricket, county cricket retains its capacity to surprise. But it might be many years before the Championship pennant next resides in a club beyond the Test-hosting elite.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, Friday April 22 2016