Hove’s first Championship was 164 years in the making

Respected cricket writer Paul Edwards goes back to the early days of the Millennium and Sussex’s first triumph in the Championship

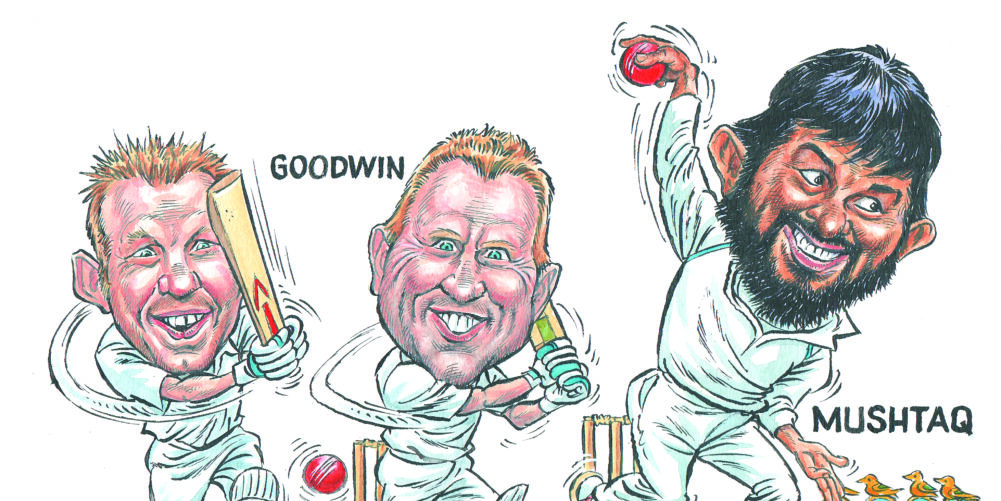

It was at 1.44 on the afternoon of September 18, 2003 that Murray Goodwin pulled Phil DeFreitas to Hove’s midwicket boundary and began a celebration which had been 164 years in the making.

Many Sussex supporters spoke of a dreamlike atmosphere as the club founded in 1839 finally won their first title. The game against Leicestershire stopped for eight minutes as Chris Adams’ team streamed onto the outfield and did a lap of great honour. The loudspeakers played the team song, Good Old Sussex By The Sea, and those spectators who were not crying too much joined in lustily.

They saluted Goodwin, Tony Cottey and Matt Prior, all of whom had made over a thousand runs in the Championship; they applauded the skipper, Chris Adams, and the director of cricket, Peter Moores, who had changed the training regime and convinced the players they could be winners.

And they cheered the leg-spinner, Mushtaq Ahmed, whose 103 wickets had made the difference. “He could open up a game that was going nowhere,” said Mark Robinson, then a member of the Sussex coaching staff.

On the morning after the title had been won, cricket writers strove nobly to capture the moment. Those Sussex supporters who had achieved fame in other fields did so, too. “I haven’t quite absorbed the shock – nor what it will mean in my own life,” admitted the playwright, David Hare, in The Guardian. “I have lived for more than 50 years with the certain conviction that I, like Sussex, will lose at everything. If Nick Hornby’s Arsenal was a kind of consolation, my Sussex has been a hideous mirror.”

Hare was too hard on the county of his birth. There had been four Gillette Cup wins and a Sunday League title to put on the Hove honours board. Sussex had finished as Championship runners-up on seven occasions. All the same, the possibility that they might win the damn thing had always seemed a trifle absurd.

Sussex, after all, had almost toyed with their supporters’ emotions for much of the 20th-century. Brilliant when expected to be poor, fallible when opportunity seemed to beckon, the county had finished in the bottom two places in the final table in ten of the post-war seasons. Yet their eccentricities did nothing to dull the loyalty of supporters who turned up at Hove, Hastings and Eastbourne, and later at Arundel and Horsham. Such quiet devotion was expressed with typical flair by the Calcutta-born poet, writer and editor, Alan Ross, who had arrived at East Grinstead to attend school in 1932 and had lost his heart to Sussex for life.

“A raffish club always, in keeping with Regency Brighton, often in the dumps, but sometimes a shooting star,” he wrote. “I suffered and rejoiced with them as over nothing else from the earliest of days.”

But if Sussex’s first title gave pleasure to lyrical poets, it was founded on the professional pragmatism and careful planning of Moores and Adams. The pair changed the culture at Hove and built a side capable of competing with both Surrey, who had won the Championship in three of the previous four seasons, and Lancashire, who lost by 252 runs at Hove in August but eventually finished runners-up.

True, centuries by Mal Loye and Stuart Law and ten wickets for Gary Keedy condemned the future champions to an innings defeat in the return match at Old Trafford, but that towsing came in the penultimate game of the season and did no more than determine the location of many knees-ups. “All it did,” concluded Wisden’s anonymous but admirably delighted Championship correspondent, “was to allow Sussex to complete their triumph memorably in front of their own enchanted supporters, rather than amid polite applause hundreds of miles from home.”

For much of the summer, though, it had seemed that the established order would prevail and that there would be nothing much to toast in Brighton’s wine bars and posh hotels that autumn. On July 12 Surrey had a 26-point lead and in late July the champions became the only team to avoid defeat at Hove in 2003 when Adams’ late declaration left the visitors needing 377 in 36 overs. Home supporters were unusually quick to criticise their skipper but Robin Martin-Jenkins recalled that match as being vital for a rather subtler reason.

“We thought we’d done the right thing,” he said. “We’d gone head to head with Surrey and we’d held our own. That was a major game for us. After that the confidence grew and grew.”

The thermometer rose as well. Pitches became drier and even more receptive to Mushtaq’s many arts. The draw against Surrey came in the middle of a nine-game run in which Sussex recorded seven victories. The county often renowned for their ability to find ways to lose had suddenly found how to win and win again. Mushtaq took 28 wickets in the next three games and Goodwin made an unbeaten double-hundred in the innings and 120-run thrashing of Essex at Colchester.

“The most important signings we made were two world-class overseas players,” said Adams of Mushtaq and Goodwin. “They should have been playing overseas cricket, and we were lucky that they didn’t.”

And as Sussex’s players grew in self-belief, Surrey’s faltered and failed. Nothing summed up the shift in fortunes more clearly than the round of matches in the first week of September. At Canterbury, Surrey lost by an innings to Kent, the match ending a mere 45 minutes into the third morning. At Hove, meanwhile, any satisfaction at their rivals’ defeat that Saturday morning was dulled by the home side’s collapse to 104-6 in reply to Middlesex’s 392.

Then Prior and Mark Davis put on 195 for the seventh wicket, the tail wagged in barely believable fashion and Sussex’s first-innings total of 537 set up a seven-wicket victory. Suddenly Surrey were playing like Sussex used to and Sussex were playing like champions.

“We won it because we wanted it more,” said Adams. “Sides like (Surrey and Lancashire) are used to winning, but we had never won it before and that was the difference.”

Even if we set aside the qualification that in 2003 Lancashire had not won the title for 69 years, the Sussex skipper’s comment requires further investigation. After all, is it not axiomatic that clubs who have won titles are used to the pressures invading a dressing room in the closing weeks of the season? Sussex had not finished in the top three since 1981 yet their players coped wonderfully well in those final matches because they did not let the occasion blunt their natural talent.

No one embodied that determination better than Adams himself, who was averaging 18 after ten Championship games yet notched four hundreds in the next six matches. Or there was the all-rounder, Martin-Jenkins, who added 811 runs to his 31 wickets. Or there were the front-line seamers James Kirtley and Jason Lewry, both of whom took over 40 wickets. When Kirtley was called up by England or suffering from shin splints, Lewry took over from him.

It was a summer when everybody was to answer the call.

Inevitably, perhaps, some sour critics forgot their own county’s indebtedness to imports and pointed to the contributions of Mushtaq and Goodwin. Sussex, though, while they are renowned as the county of families, are also the team for which Ranjitsinhji, Duleepsinhji, Alan Melville and Imran Khan played, most of them doing so long before it was the fashion to engage overseas players.

If the heart of Sussex cricket can be found on the Downs in high summer or at Hove in a May sea-fret, its nerves and senses stretch around the globe. It was rather appropriate that while the club’s members were still ordering more bottles of Pol Roger to celebrate the arrival of the title, Goodwin went on to set a new record individual score for the county, his 335 not out eclipsing Duleepsinhji’s 333 against Northamptonshire in 1930.

Many neutrals were delighted that the oldest county had finally won the title. Indeed, has any Championship triumph been celebrated quite as warmly outside the borders of the title-winning county? Certainly it was toasted, albeit with nothing more exotic than a mug of coffee, in a garden in Southport that September afternoon.

For, although born in Sussex, I only stayed there about five minutes before my parents moved to Oldham. Nevertheless, one of my confused loyalties had been pledged and throughout a cricket-crazy childhood, it was the results of the teams led by Mike Griffiths and Tony Greig that I followed most keenly.

My fondness, though, was expressed from a distance, just as it is with many other county supporters. During summers spent in necessary exile, they read about their team’s fortunes on the internet and post messages of love below the reports.

Unless they follow Yorkshire, Surrey or Middlesex, they are reconciled to mild disappointment.

In my case, the likelihood of Sussex ever winning the title seemed roughly comparable to my own chances of ever earning a living by writing about the game.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, January 6 2017

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here