Emma John knew nothing but defeat as a fan of 90s England. But were Atherton’s Army really that bad?

It can take a long time to heal sporting heartbreak. Just ask Gareth Southgate, or Nick Hornby. As for England cricket followers, it’s taken us 20 years to be able to look back with any affection on the 1990s. For a long time, even those who selected the archive footage for use during rain delays seemed to regard it as an untouchable era.

But it seems that time has now come and – much like Justin Bieber – we’re finally ready to confront our awkward past. This week, Mark Butcher presented Sky Sports’ first documentary on the Atherton, Stewart and Hussain years. When you consider how many 90s players make up its presenting team, it’s a wonder it’s taken this long. Their failures have, after all, been an endless source of banter, of wry comments about who did worse against New Zealand, or how often Shane Warne got them out.

We, meanwhile, wear our knowledge of the 90s like a military medal, a collective experience of trauma. We recall its endless carousel of players – remember Alan Wells? Mike Smith? Joey Benjamin? – like old campaigners talking of lost comrades.

The history books don’t dwell too much on this inglorious period. It was a downbeat tale, of emotionally fragile batsmen, left-arm medium pacers, and second-hand Australians, and once the 2005 Ashes came along, we’d learnt all we needed from the previous England set-up’s self-defeating method. The 90s had taught us plenty about the need for proper management and central contracts; about how, in short, not to run a national sport.

But there was one more lesson that only perspective, and the passage of time, could bring. And it’s a surprising one. It is that –whisper it quietly – 90s England weren’t as bad as we think they were.

As someone who only came to the game in 1993 – post-Brearley, post-Gower – my vision was clouded. I supported a team whose identity was built on what they failed to win – the Ashes, or any Test series of note. As a girl with limited life experience, I believed, with dismal fervour, that England wouldn’t beat Australia again in my lifetime.

We held these truths to be self-evident: England’s 90s players were losers. But only in retrospect have we been able to understand how great their opposition were. The decline in standards of pace bowling, and the inability of any spinner since to pick up the mantle of Shane Warne or Muttiah Muralitharan, has revealed that England fans of the 90s were living in a golden age of cricket. It just wasn’t golden for us.

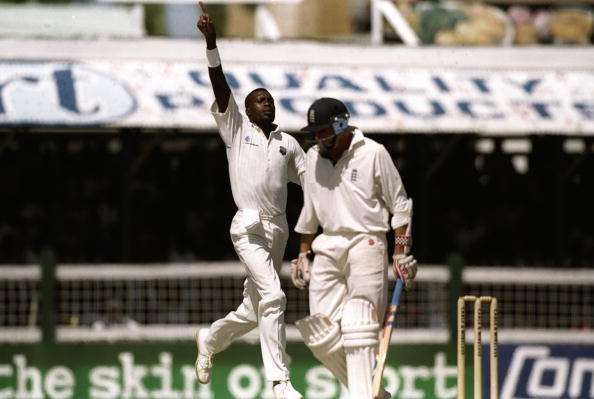

There were indomitable bowling attacks wherever you looked. South Africa had Allan Donald and Shaun Pollock, Pakistan had Wasim and Waqar, West Indies, Curtly and Courtney. In Warne and Murali the decade held arguably the two greatest spinners of all time, and indubitably Test cricket’s deadliest wicket-takers. In Sachin Tendulkar and Brian Lara, the game was blessed with not one but two batsmen of a generation.

If that were not enough, it was also the decade that Steve Waugh’s record-breaking Untouchables were forged. England may have lost every Ashes they played, but it’s hard to blame them when, by the end of the 90s, Australia had built one of the great teams in Test history, a side who would later have the country debating whether they were greater than Bradman’s Invincibles.

While writing my book about England under Mike Atherton, I spoke to 12 defining players – from Graham Thorpe and Jack Russell to Dominic Cork and Nasser Hussain – and all of them agreed that, despite the poor results, they wouldn’t have chosen to play in any other era. Why? Because it was the greatest challenge they could have faced.

“You will always suffer by comparison, it goes without saying,” Andrew Caddick told me. “And most of the England guys would say the same: you played against some serious players. The standard of world cricket was a lot higher than now. When you had the West Indies pace bowling quartet, Shoaib Akhtar, Brett Lee, Glenn McGrath, Craig McDermott… that was seriously high-quality cricket.”

The stats agree. Take a look at the ICC’s historic player rankings, and five of the 11 bowlers with the highest peak ratings of all time played the majority of their cricket in the 90s: Murali, Ambrose, McGrath, Waqar Younis and Shaun Pollock. The batsmen who did well in the 90s – and whose reputations have lived on in spite of the defeats – were those bloody-minded few who relished the onslaught: Graham Thorpe, Alec Stewart, Mike Atherton, Nasser Hussain.

“I looked at who was getting me out – Pollock, Waqar, Warne, Ambrose – and I didn’t think I was doing much wrong,” said Thorpe when we chatted. “When you look back at the runs you scored against those attacks, and when you look at their bowling stats, you realise it was a pretty tough era… We were a little bit amateurish (in our organisation), but the quality of the cricket on the pitch always seemed good.”

England’s bowlers had their problems, not least Brian Lara. When Wisden compiled their 100 greatest innings in 2001, the West Indies genius made it into the top ten twice (only Sir Don Bradman did likewise). Aside from him and Tendulkar, there were plenty of other destructive batsmen, from Michael Slater to Lance Klusener, Andy Flower to Inzamam-ul-Haq, Sanath Jayasuriya to VVS Laxman – and yet, averages were low across the board compared to other decades. As for centuries, the number of 100s per innings scored by the top seven batsmen in each country was 25 per cent lower than in the 2000s.

There’s a second secret to the story of 1990s England, one that has been almost universally overlooked. The team were worse in the 1980s. The bald truth is that England’s 90s Test team has a better win-loss ratio (won 26, lost 43) than that of the previous decade (won 20, lost 39). From 1987 to 1989, England managed to play 25 Tests, lose 11 and win one against Sri Lanka at Lord’s. But the poor record of the 80s is obscured by three Ashes wins, which gilded the era of Gower, Gooch and Gatting more than it deserved.

The 80s made heroes of Ian Botham, David Gower and Graham Gooch. England in the 90s had their heroes: Stewart, for instance, scored more Test runs in the 90s than anyone in the world (by dint, largely, of how many games he played – but still, he beat both Waughs) and was England’s second-highest Test runscorer of all time at his retirement. Yet it was hard to appreciate their achievements when Tendulkar was breaking records, Ambrose was breaking bones, and Shane Warne was breaking everyone’s will to live.

We tend to think of the 90s as Atherton’s decade, so perhaps it’s appropriate that he should have the last word. His career spanned 1989-2001 and, while this may surprise some, he managed to play in a series-winning side against every Test nation except Australia (and Bangladesh, who he never faced). When we met, I asked him if he thought England’s 90s reputation was a little harsh. “Broadly speaking we did pretty well against the teams we matched up to,” he said. “South Africa were a strong team but we were pretty evenly matched – they may have had the edge. Pakistan and Australia were better than us, and I thought we were better than India and Sri Lanka. Obviously what you hope to do is play slightly above your level.”

England certainly didn’t do that regularly. But their Test wins and individual performances, against some of the great cricketers that the world has seen, mean that it’s fair to indulge in at least a little revisionist history. Now, hand me those rose-tinted spectacles…

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, Friday May 20 2016