By Guy Williams

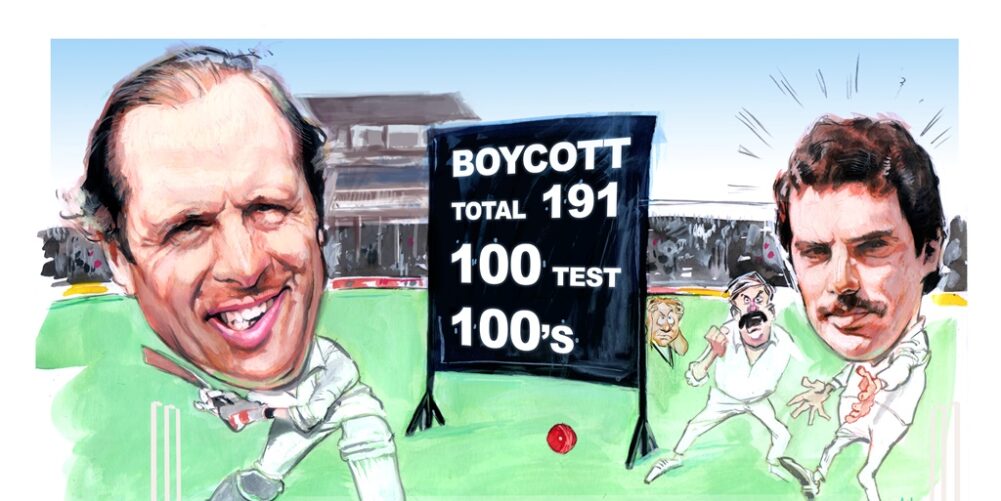

Forty years ago, last Friday, at Headingley – to be precise at 5.49 in the late afternoon – Geoffrey Boycott, the Yorkshire and England opener, on-drove a four to complete a unique and emotional century which established a new record in cricket history.

As Boycott stroked the ball to the boundary, he became the only batsman to reach his 100th hundred in a Test match, and instantly joined the 17 other great batsmen who shared the remarkable distinction of 100 first-class centuries or more.

Boycott’s four off the medium pace bowling of Australian captain Greg Chappell was also extra special because his century was achieved on his home ground where thousands of supporters, dozens of whom invaded the pitch, cheered and applauded their Yorkshire hero – one of cricket’s most controversial characters in the post-war game.

Indeed, play was interrupted for seven minutes as if a period of reflection was required to absorb the magnitude of Boycott’s achievement, watched live on BBC television and heard by thousands at work and at home listening to Test Match Special.

Many of today’s T20 and Twitter generation know Boycott, a fit and healthy 76-year-old, as a blunt, highly entertaining and knowledgeable commentator, but may be unaware they are listening to or reading the views of a world-class batsman whose pursuit of hundreds in his career (1962-1986) was as ruthless as Don Bradman’s.

As his famous innings dominated the back pages and figured prominently in national news bulletins, its significance expanded. By the time he was eventually out for 191, Boycott, since his recall after voluntarily missing 30 Tests following a disagreement with England’s selectors, had batted 22 and a half hours at Trent Bridge and then Headingley, and in the process had compiled scores of 107, 80 and 191.

No wonder then that Boycott’s application, concentration, caution and masterful technique contributed hugely to England regaining the Ashes.

His memorable innings may have been 40 years ago, but Boycott typically remembers every detail only too clearly. Firstly, though, he emphasises the foundations had been laid in the previous Test at Trent Bridge.

“I would say that my comeback at Nottingham was the most difficult and hardest innings I’ve played. I’d been away from Test cricket for three years and some people were finding it hard to forgive me for not playing for England.

I was also 36 years of age, and most players are retiring at 36. Age catches up with you and your reflexes are not as quick, so batting gets harder. I knew Jeff Thomson and Len Pascoe, both genuine quick bowlers, were going to test out whether I still had the courage and the technique to handle the short stuff.

“Then, there were no limitations on short balls. Now the limit is two an over.

It was a test of my ability and if I’d failed, some people and the media would have said ‘Boycott’s not that good anyhow’. So there was a lot riding on it, and if that wasn’t enough I then ran out Derek Randall, the local hero, on 13. It was a nightmare.

“But I had enough mental toughness to get me through. I got a 100, Alan Knott also got a hundred and we won.

“It was a test of character and to come through was a relief. That was my 98th century, and then I had a few days off and went on to score my 99th against Warwickshire.

“Rachel, now my wife, then rang me and said you’ve done it now, but I didn’t realise what. She said it had already been on the news that I was going to get my 100th hundred in the next Test at Headingley. I thought, ‘no, I’ve just gone through the most pressure I’ve ever had and now there’s even more…home ground, home supporters, Australia and the expectation that I’d get another’. It was all a piece of cake, but it wasn’t.

“I was so uptight at the team meeting the evening before and I told Mike Brearley, the captain, that I needed to go, I struggled to sleep because of the tension and pressure. I woke up at four in the morning, tense and nervous, but having nerves is normal. It shows you care and the great players handle those nerves.

“I was late getting up and rushed to Headingley where Keith Boyce, the groundsman, was taking the nets down. So I asked him to leave one up so I could have a knock. I batted for seven minutes against local bowlers and then went into the dressing room where Mike said we were batting. I was hoping we’d field.

“Mike got out quickly. I was nervous, but after about 25 minutes I felt great and the ball was hitting the middle of the bat. I was in control and got into a cocoon of concentration and nothing bothered me.The odds were huge that I’d get a 100 in the Test, but if I got in everyone was expecting me to do so. I knew the crowd were with me and that added to the stress and tension.

“I batted in sections: getting off the mark, getting to 10 and then 20. I didn’t get too far ahead of myself, but I always batted to score hundreds. I knew Chappell was going to put himself on because the main bowlers hadn’t got me out.

“I’d picked three areas where I was going to hit it because they were safe and I’ve always believed if you get into the 90s, there should be no thing as being nervous. You’ve been batting for a few hours and should be in control.

“Chappell bowled it just outside the off-stump at the Kirskstall Lane End and I hit it past the stumps on the other side. The ball was half way down the pitch and I knew I was going to hit it, and where.

“It’s a magical moment that happens only a few times in your career when you know exactly what you are going to do before you’ve done it. It was the best moment in my career – something historic that hadn’t been done before.

“Afterwards, I remember going back to the hotel in the centre of Leeds and rang Brian Clough and Michael Parkinson, two good friends. Cloughie missed a Nottingham Forest committee meeting to watch me bat all day. Tim Rice delivered a big bottle of champagne and the England team went in for dinner at 7.30pm into the casino where the food was lovely, but we were the only people there at that hour.”

Boycott’s distinction was subsequently equalled by Zaheer Abbas, the Pakistan and Gloucestershire batsman, who reached his 100th century in a Test against India in 1982/83.

“I don’t think there’ll be enough first-class games to get 100 hundreds in the future,” says Boycott.

“County cricket is being squeezed and that will happen more and more. The game has changed alarmingly. Is it for the better? I’m not so sure. I think there’ll be different types of records. Kids are growing up talking about records in T20. How many sixes did you hit? How many balls did you receive? What’s the run rate? They are playing so much more one-day cricket now.

“But you can’t live in the past. I get up and am very happy to go to the cricket and you’ve got to look at cricket as it is.The game has always changed. The laws have changed, pitches have changed and bats have changed. You’ve got to enjoy cricket as it is.”

Boycott is marking the 40th anniversary of his special innings by organising two charity events to raise money for the Yorkshire Air Ambulance and Martin House Children’s Hospice in Boston Spa, near Leeds, where he lives.