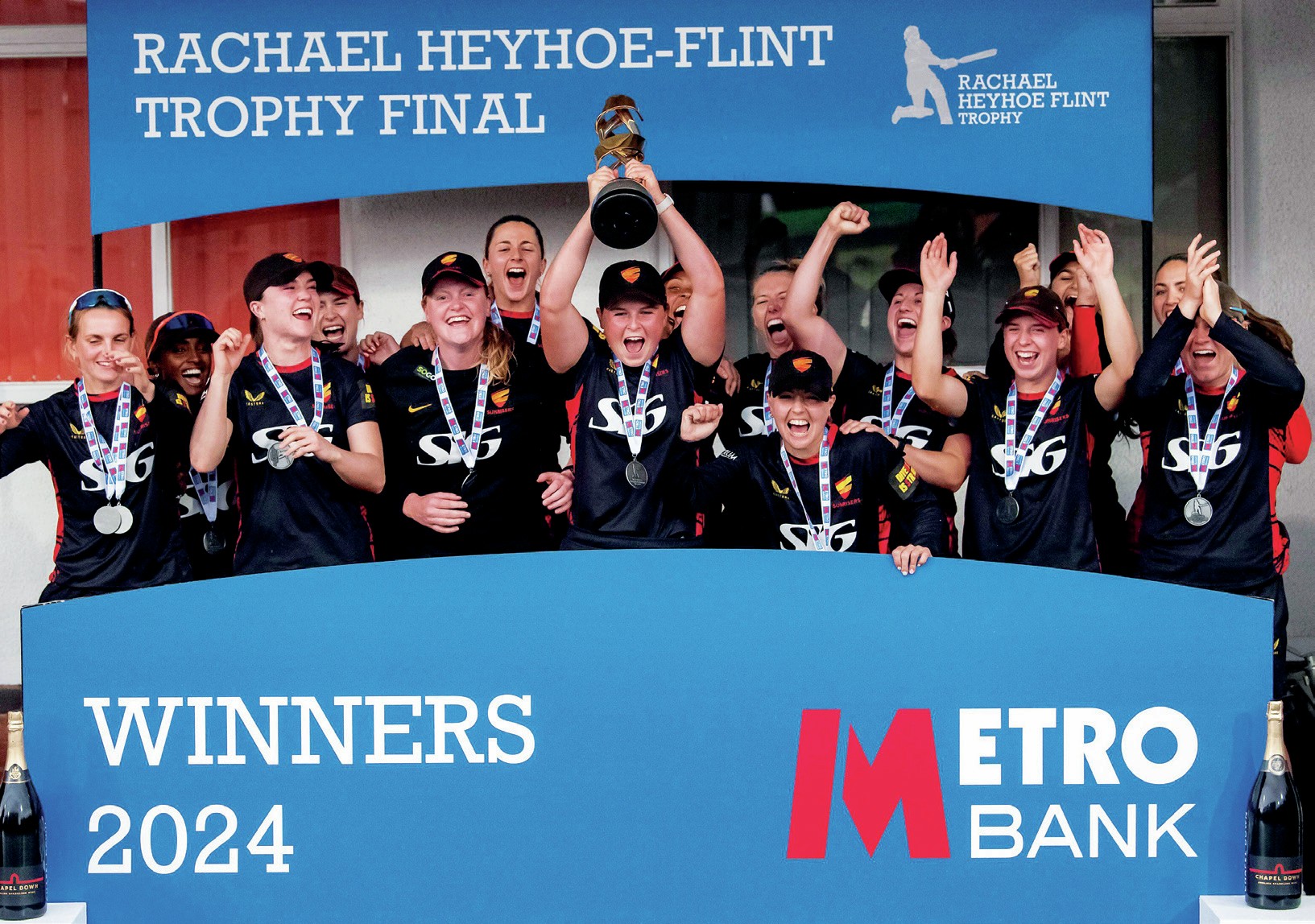

(Photo: Getty Images)

By Derek Pringle

There are five rounds of County Championship matches before the start of June – a sizeable chunk of the programme that could prove vital in determining the destination of this season’s title given the vagaries of pitches, weather and form at this time of year.

Traditionally, early season encounters in the Championship have been decided by seam bowlers. With the moisture from spring rain yet to be evaporated by summer heat, pitches tend to retain a good covering of live grass in April and May, conditions perfect for exploitation by those with a stable wrist and the steadfast constitution to plug away with line and length.

But having the means and the right environment doesn’t always guarantee success and countering the widespread expectation that seamers will “do the business” before June brings a pressure that can tense-up actions and buckle resolve in even the most bullish performer.

That is when the value of a senior pro presents itself, a role John Lever fulfilled with the Essex teams which won three Championships in the 1980s. Not only was Lever a leader in setting an example with his unstinting swing bowling, both early season and beyond, but he would quell fears in others with homilies like – “Rather bowl on a green one than a flat one,” and simple affirmations like “cash in when you can.”

One basic all seam bowlers must observe on pitches offering assistance is a full length. Allowing batsmen to play forward on a flat one may be a symbol of a bowler losing their personal battle with them, but not when the ball is flirting about off the seam. Then, drawing them on to the front foot means they have less time to adjust either their shot or their decision-making. There is also less time, in the time and motion relationship, for the ball’s movement to miss the edge of the bat.

Put simply, when the ball is doing a bit, you don’t want batsmen to play more than 10 per cent of their shots off the back foot. Anything more and you are making life easier for them.

Not that a full, probing length is easy for every bowler to dial into. Some pace bowlers’ actions naturally alight on a length that is shorter than the optimum for a green seamer. Andy Caddick, a tall pace bowler for Somerset and England, had a natural trajectory and length more suited to true pitches, where containment is important.

On helpful surfaces he would beat batsmen all ends up but due to the mechanics of his action found it difficult to adjust to a fuller, edge-finding length, and still retain the same vim in his bowling. In contrast, Darren Gough had a natural length that was further up which meant when the ball moved around he tended to get batsmen out more often as a consequence.

A similar comparison could once have been made between James Anderson and Stuart Broad. But as Broad showed when he cut through Australia at Trent Bridge three years ago with eight for 15, he has subsequently been able to adjust his length accordingly with match-winning consequences.

On such occasions seam is more difficult to combat than swing as the movement, whose direction even the bowler is unable to discern, is much later. That means the batsmen cannot adjust in any meaningful way, which is why Australia’s looked like rabbits in the headlights at Nottingham when confronted with such controlled mastery.

That pitch at Trent Bridge wasn’t early season, which made it more difficult as there was pace and bounce, and therefore good carry, to be factored into the degree of difficulty equation. Generally, early season pitches lack both pace and bounce, which gives the most technically adept batsmen at least something to work with in their attempts to build a score in challenging conditions.

Slip in: Trent Bridge can be a seamer’s dream (photo: Harry Trump/Getty Images)

Like the bowlers there are a few basic things the batsmen can utilise to combat the sporty pitches one tends to find in the first six or seven weeks of the season. The first is discipline, and the necessity to cut out front foot drives unless the ball is right under their nose or has stopped moving. Another is patience and having the restraint to wait for that short ball which can be despatched with more certainty and control.

The other thing to be mindful of is playing the ball as late as possible. When the ball is moving about, letting the ball hit the bat when the latter is at an acute angle not beyond the perpendicular, is key to minimising the chances of one’s dismissal, especially caught off the edge, the prime mode of getting out during April and May along with lbw.

One thing many of the best batsmen do when the ball is seaming about, is play the line of the ball but hold their defensive shot once it moves. It can be difficult to do given most batsmen’s instinct is to put bat to ball. But following the ball once it has deviated off the straight, especially if that movement is away from the bat, simply invites peril as many can testify.

It can be hard work for batsmen early doors which is why the old challenge of 1,000 runs before the end of May was considered such a fine feat. Only nine men have done it, including Don Bradman who managed it twice, and WG Grace who did it when he was 46 years old. In modern times, Graeme Hick reached the mark in 1988 but that was the last time it happened, with Nick Compton coming closest in 2012 when he reached his 1,000th run on June 1, just one day too late after rain prevented him taking the crease 24 hours earlier.

The batsman’s lot has improved since then, in theory, due to the disposal of the toss (unless both teams want to bat), which has reduced the instances of groundsmen producing bowler-friendly pitches for the home side. But heavy rain so far, and a long-range forecast threatening even more, means pitch preparation could be in the lap of the gods, which could favour visiting teams a lot over the early skirmishes given their current privilege of bowling first if they wish.

Despite that, the first five rounds promises plenty of fascinating drama as teams work out whether boldness, caution, calm, consistency and driving with due care and attention, is the best way to get their season off to a roaring start.